The present year [1956] marks the centenary of the issue of one of the most interesting and perhaps the least understood of the several series of coins issued in China in the endeavor to align its coinage with occidental monetary practices. It seems therefore appropriate to commemorate that event by the publication of some newly discovered literary evidence, which although originally published some 95 years ago, appears never before to have come to the attention of any of the several numismatists who have interested themselves in the tael and half-tael silver coins struck in Shanghai in 1856. The author has supplemented this by notes on the same subject which have been collected over the past decade.

The Shanghai coins of the 1856 issue appear to have been published first by Alexander Wylie in a paper laid before the Shanghai Literary and Scientific Society, the predecessor of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, on November 17, 1857, which was subsequently printed in the first volume of the journal of the Society in June 1858. Only one denomination, the one-tael, and only one variety of that was known to Wylie, although he was then an active coin collector and was living in Shanghai. The information given by Wylie with respect to this coin was copied by J.H.S.Lockhart in his catalog and description of the Glover Collection (1895), where a specimen numbered 1237 is illustrated. This specimen is not now in this collection, the major portion of which was deposited in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

In an article entitled "The Coins of Shanghai, an Unwritten Chapter in the History of the 'Capital of the Far East'", by A.M.Tracey Woodward, originally published in the August 1937 issue of The China Journal and subsequently reprinted as Bulletin Number 3 of the Numismatic Society of China, he decried the meagerness of contemporary published notices of the earlier issues. It would appear that he had overlooked the writings of a keen observer of the passing scene in Shanghai in the late 1850's, Dr. William Lockhart, of the London Missionary Society. Published in his book, The Medical Missionary of China; A Narrative of Twenty Year's Experience (London 1861), is truly an eyewitness description of the actual minting of these particular coins. As this does not seem to have been taken into account by anyone previously when writing on the subject of these coins, it is quoted in full:

“Dollars are made occasionally for particular purposes, as lately in Shanghai, when the old Carolus dollars became so scarce that silver coin was wanted for the carrying on of trade. The local government resolved to coin money, of the weight of a tael, an ounce and a third of silver. This was pure sycee, or unalloyed silver, and proved to be too soft for continued use. This coin was first taken by the people, who, however, after all the trouble and expense of coining, when they received it in any large quantity, returned it to the crucible, and melted into the usual shoe-shaped ingots; in consequence of which the coining ceased.

Discs of silver for the production of this coin were first made by running the metal into flat moulds on iron plates, which closed like common bullet-moulds, each set of plates having three moulds. These discs, after the weight was proved – if over or under weight they were at once returned to the melting pot – were hammered flat, and made as true as possible by the use of the file, so that when finished they were perfectly smooth, and of one size. The pieces of silver were now taken to the stamping press, where they were impressed with rows of Chinese characters, stating the weight, place of coinage, the maker, and the name of his bank or assay office, the local officer, the date, and the name of the emperor.

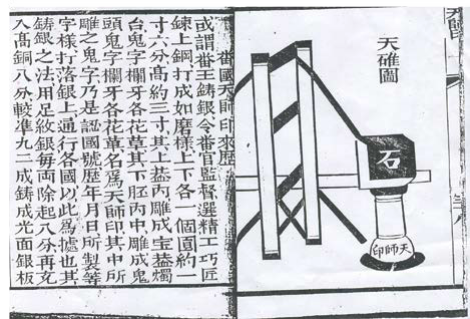

The die for these impressions consisted of two parts, the obverse and reverse, which are cut on the faces of two pieces of steel, square, and a little larger than the silver discs. The reverse has steel sides made to it, in the form of a square box, with the corners open, into which box the obverse die exactly fits, being kept in its place by the sides. The press had a large block of granite for a stamping stool, and affixed to it a perpendicular slide about ten feet high, across the top of which is a piece of wood, well oiled, and, some little distance off, a powerful winch. The stamping weight consists of a block of granite about 200 pounds in weight, and beveled off at the top so that a hole may be bored through. A strong rope attached to the winch and passing over the slide is fastened to the top of the stone, which, when hoisted to its place, is held there until it is required by a peg in the slide.

A thick piece of folded paper is laid over the lower stone, upon which is placed the box-like die, with a silver disk inside. The obverse (die) is then fixed, covered on the top or outside with another thick piece of folded paper. When all is ready, the peg is drawn out from the slide, and the stone mass falls on the die, impressing the coin very efficiently. The stone is then hoisted for another disk to be placed, and so the work of stamping the coins proceeds.

The coins were milled (reeded) at the edge with a cross pattern, in a very simple manner. The pattern, cut on a narrow slip of steel eight inches long, is fixed at the bottom of an angular iron groove of the same length, to enable the coin to run readily along the groove on the slip of steel. A man, with one of the finished coins between his thumb and finger, as it rolls along the groove, strikes its upper edge with a light wooden hammer. In this way the pattern on the steel is impressed on the edge, and the coin, now complete, is taken to the office for examination and distribution.”

There can be no doubt but that Lockhart was actually present to witness the processes of their manufacture in the 6th year of Hsien Feng (Feb.6, 1856-Jan. 25, 1857), as it is related in Memorials of Protestant Missionaries to the Chinese, a publication of the American Presbyterian Mission Press of Shanghai, 1867, that "In the beginning of December 1857, Mr. Lockhart left Shanghai for his native land, and… reached England on the 29th of January 1858." It is regretted that even so meticulous an observer as Lockhart failed to record exactly where in Shanghai the coining was done, as the location of the hong which made the coins and whether or not it was located within the confines of the walled native city of Shanghai or inside the foreign Settlement, would be of great interest. Woodward believed that it was located inside the walled city. This is open to question as the walled city had been captured by the Triad rebels on September 4, 1853, and remained in their possession until February 17, 1855. The Chinese custom house, located inside the Settlement, was looted and burned by the Triads in a sortie on September 7, 1853. The custom house was thereafter temporarily located on board a junk moored opposite the Settlement until February 9, 1854, when it relocated ashore inside the International Settlement near Soochow Creek. It seems highly improbable that the Lu Fang delegated by the Chinese authorities to make these coins would have removed to the native city so soon after it was reoccupied by the imperial forces, and particularly so as at the time the T'ai-p'ing rebel forces were still operating in the environs of Shanghai. Having already lost a half million taels of silver to the Triads when the native city was first captured, it seems improbable that the treasury would have been returned to the city, where they would no longer enjoy the safety provided by the warships and armed forces of the European powers.

As the original article by Woodward, mentioned above, may not be available to all interested readers, the pertinent portions are quoted herewith, with minor changes in his orthography. For those who refer to the original article it will be noted that the romanization of the Chinese characters in some instances differs from that given by him. Woodward's romanization of the Chinese characters which are principally those found on the coins, appears to be in the Shanghai dialect rather than Mandarin, and this is probably due to his having employed a Chinese scribe who was not proficient in Mandarin. All Chinese characters in this article, however, are transliterated according to Giles in the Wade system.

“The 'native issues' came into existence toward the close of 1856, and it is regretted that Wylie, writing at so close a date as the middle of 1857, gave but little attention to them. I may be pardoned for quoting him in full 80 years later, considering that he is apparently the only foreign authority who can be reliably consulted. However, he refers only to the coin here designated as Type A, as, indeed does Lockhart in describing the Glover collection, and Ros in his lecture read in Hankow on December 3, 1921, whilst every writer who took part in the controversy published in the "North[1]China Daily News" of October 1919, refers to the same coin only. All that Wylie says in describing the coin is that it is of a tael weight, produced in Shanghai under the direction of the Intendant of Circuit, about the end of the year 1856. It is struck from a steel die, and tolerably well executed; but it had scarcely made its appearance, when spurious imitations of baser metal were put in joint circulation with it, so that confidence in the new coin was speedily at an end, and it is now only to be found as a numismatic specimen.”

Woodward's text, quoted above, is misleading in that it is not "all that Wylie says in describing the coin. "Wylie went on to quote completely the Chinese inscriptions on both faces of the coin and to give a quite adequate translation, as follows:

“The inscription on the obverse is Hsien feng liu nien / Shang hai hsien hao / shang Wong Yung-sheng / tsu wen yin ping (Hsien-feng 6th year; a cake of pure sycee silver, from the firm of Wong Yung Sheng, in the district of Shanghai). The reverse has Chu yuan-yu chien / ch'ing ts'ao ping shih / chung yi liang yin / chiang Wan Ch'uan tsao (one ounce of silver, true weight by the ordinary balance, cast under the inspection of Chu Yuan-yu, and executed by Wan Ch'uan, silversmith)”

I have taken the liberty of modifying Wylie's romanization of the Chinese characters to conform to the Wade system, which had not been invented at the time he wrote, 98 years ago. I have my own personal regrets to record now that I am interested in Chinese coins, as I note that Woodward mentions a lecture given before the Union Church Literary Guild in Hankow on the subject of "Modern Chinese Coinage "by Giuseppe Ros on December 3, 1921. A diligent search for the text of this lecture, which may have been published in either the local press or in one of the omnibus publications which were so popular at that time among literary clubs in China, has failed to produce any results. I was a resident of Hankow during the years 1923- 24, and could without doubt have obtained this item (if it was printed) so soon after its delivery.

Continuing to quote Woodward's article:

“The coin alluded to by earlier authorities was not the only one that was made in the sixth year of Hsien Feng (1856), and although all the varieties were produced under the auspices and inspection of one Chu Yuan-yu, who was sometimes given the rank or title of Intendant of Circuit, Intendant of Mint, and even Intendant of Finance, the coins were, nevertheless, not all issued by one hong, nor made by the same engraver. I have searched in vain among native annals for details and records bearing on these coins. No trace appears to have been preserved of the number issued, nor the reason for their appearance (we only know the fact that they were mostly employed for payment of the military), nor is it even known in what precise localities in Shanghai the authorized issuing hongs were located, although it is generally admitted that they were situated within the now destroyed city walls of Shanghai City. Indeed, time seems to have erased all traces that today would be considered so precious. We have only the coins, of which, even so, very few are in existence, owing to the constant activities in the last thirty years of the sycee casting houses known as the Yin Lu.

The coins were issued by three hongs, and the preparation of the dies was also done by three engravers, although no proof exists that each hong had its exclusive engraver. (I say three hongs, basing my statement on the names so far revealed from the coins, but in China where surprises in numismatics are constant, it lies within the bounds of possibility that more hongs may have also caused an issue. The same remarks may be applied to the engravers but with greater probability.). Quite the contrary, for it will be observed that two hongs, Ching Cheng Chi and Yu Sen Sheng, employed the same engravers, Feng Nien and Wang Shou. As to the number of dies employed, it may be said with some degree of assurance, that not more than one was made for each of the one tael varieties, the differences in engraving marking the forgeries mentioned by Wylie.

The native script on the good coins is on a plain field without milling. The rims are grained (reeded) with a mosaic pattern, the whole giving the coins a true touch of dignity in its serene simplicity. It is certainly typically oriental. Type A denotes the coin which has heretofore always been referred to by writers, and the piece here illustrated [in the Woodward article] is the actual one which adorned the collection of the late S. W. Bushell for many years ….. Its weight is 563.3 grains, but I have scaled some pieces as high as 566.24 grains ….. There is a good illustration of this piece in cast formation by means of the galvanic battery and impressed on silver paper in "The Current Gold and Silver Coins of All Countries", wherein the weight of the piece is given as 565 grains troy with the remarkable fineness of 990 milliemes, thus making it a 15-5/8 “betterness” than the British standard purity of silver coins [which is 11 ounces 2 pennyweight or 37/40 fine, the equivalent of 925 milliemes.]”

Past publications of the half-tael varieties seemingly have been inadequate. There is a marked distinction between two varieties of these coins, aside from the differing texts of inscriptions, which does not seem to have been given cognizance by previous commentators. These are characterized by the lack of the thick broad rims which are found on all of the one tael pieces and on most of the half tael denominations. The inscriptions on these two varieties are bounded by an area with overall dimensions of 25x25 mm, as in the one tael pieces, while the comparable dimensions of the texts of the rimmed half-tael varieties is only 21x21 mm. These were struck by using the identical obverse dies, la and b, which were used for the one-tael pieces, together with new reverse dies, one of which has the engraver's name, Wan Chuan, and the character of denomination in the hsiao k’ai form, while the second has the engraver's name, Wang Shou, and the character of value in the ta k'ai form. Both of these varieties were struck on flans somewhat thinner and slightly greater in diameter than those used for the rimmed varieties having similar inscriptions. It seems probable that these were the earliest half-tael pieces coined, and being found unsatisfactory due to the difference in appearance as compared with the concurrently circulated one tael pieces, and because the lack of the outer rims, which inhibited undue wearing of the Chinese characters composing the inscriptions. Other obverse and reverse dies were made by the same engravers with similar inscriptions measuring 21x21 mm.

The Yu Sen Sheng variety of the half-tael was figured by Woodward as "Type G" (column 3, table 1). The identical Woodward specimen is now in my collection. Woodward published a picture of what he termed another variety of this type, as "Type F," but failed to establish definitely the type of its reeding, his text stating it to be his ZA style reeding while his tabulation indicates by means of a dash that he did not know what style of reeding was on the coin. He further stated that his illustration for this "Type F" specimen was "from a good rubbing." A careful examination fails to confirm this statement, as there is every indication that the illustration was not from a rubbing but from a handmade copy made with a Chinese brush. It is just possible that it was made from an indistinct rubbing which had the Chinese characters touched up with a brush, but even this seems doubtful. It is accordingly concluded that he never even saw this particular specimen, but relied upon the statement of some collector, probably a Chinese, that he had such a coin, which in the nature of things is perhaps the world's worst evidence and worthy of no consideration.

With respect to the Wang Yung Sheng variety of the rimless half-tael denomination (column l, table 1), when Kalgan Shih visited the United States in 1947 he had in his possession and gave me a photograph of the specimen he had in his collection. It is noted that he has not included it in either edition of his Modern Coins of China [1949; 2nd ed. 1951], although he has included the Yu Sen Sheng specimen, described above, as his number C10-4.

Theories have been advanced to the effect that these coins were made by separate hongs because of the three different names, Wang Yung Sheng (column l, table 1), Yu Sen Sheng (column 3, table 1), and Ching Chung Chi (column 5, table 1), which appear on the obverses. After considering the somewhat elaborate and expensive, though crude, machine and accessories which Lockhart so fully described, and the well-known facts which characterized the operations of trade guilds in China, it is believed that such a project would most probably have been carried out on a cooperative basis. It is therefore concluded that all of these coins were made in one plant or mint, and that the different names appearing on them are indicative of the responsibilities of the respective hongs with respect to the touch of the silver entering into the manufacture of the coins. This is borne out by the fact that the three hongs appear to have used several of the reverse dies indiscriminately. Such a use of the dies could only have taken place if the coins all were minted in one place.

The description given by Lockhart of the method employed in the applying of the reeding on these coins, was done in a simple fashion, which is typically Chinese in its employment of handwork assisted by the simplest tools. In this case the tools consisted of a wooden mallet and a grooved steel channel, with the simple zigzag pattern of the reeding desired, in relief at its bottom. The blows of the mallet driving the edge of the coin into the interstices of the reeding die caused a series of short flat surfaces to be impressed on the edge of the coin, rather than the smooth even circle resulting from the conventional collars employed by mechanical minting machinery.

These surfaces have the impressions of the reeding die impressed upon them, and taken together give the impression of continuous triple zigzag lines. However, if the coin is revolved between the thumb and fingers, the intermittent character of the finished edge is readily apparent. Usually there is a slight overlapping of the pattern at the place where the contact with the die started and finished, which causes a doubling of the pattern over the length of the overlap.

The tactile test, described above, of rotating the coin between the thumb and fingers, is believed to be one of the simplest and surest ways of detecting forgeries which are other than of the crudest sort. If the coin's edge does not have the flat facets but is smoothly circular, the chances are that it is not a genuine specimen.

Reeding dies of different gauges were employed in finishing the tael and half-tael coins, which vary in the length of each component part of the meandering pattern, as well as in the width. These have an average width of 3 mm for the tael and 2 mm for the half tael, while the average length of each segment of the pattern is respectively 5.8 mm and 4.0 mm.

It will be perceived that the flat raised marginal rims of the coins served a practical purpose in the reeding process, acting as guides while the reeding was applied. The grooves were not tight enough to hold the coins in a precisely vertical position while the hammering was being done, as is evidenced by the fact that the finished edges are sometimes not exactly at right angles to the face of the coin throughout its circumference, due to their having been held at a slight angle while the blows of the mallet were being struck. It will also be noted that the impressions of the grooved reeding die does not always obliterate the marks of the files which were used on the edges in truing up the cast silver planchets and bringing the slightly overweight pieces within the wanted tolerance with respect to their passing weight.

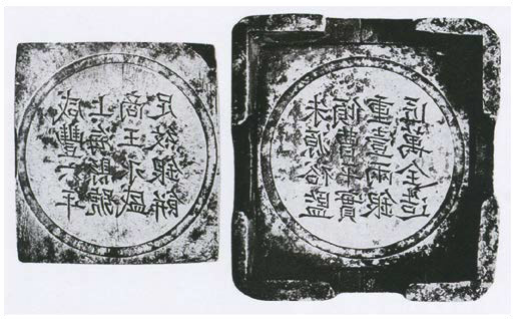

Figure 1 (obverse and reverse), represents the dies from which the first published specimen was reported by Wylie, and also Woodward's Type A, the one tael denomination. The characters are read from top to bottom commencing with the right hand columns a and e.

圖1

|

d |

c |

b |

a |

|

h |

g |

f |

e |

|

足 |

商 |

上 |

咸 |

|

匠 |

重 |

傾 |

朱 |

|

紋 |

王 |

海 |

豐 |

|

萬 |

壹 |

曹 |

源 |

|

銀 |

永 |

縣 |

六 |

|

全 |

兩 |

平 |

裕 |

|

餅 |

盛 |

號 |

年 |

|

造 |

銀 |

寶 |

監 |

|

I Obverse |

|

II Reverse |

||||||

The obverse is considered to be the side with four Chinese characters Hsien Feng Liu Nien, indicating the date of issue, 1856, in column a. The names of the hongs under whose cognizance the coins were made appear in the second, third and fourth characters of column c. These consist of the combinations Wang Yung Sheng, column 1; Yu Sen Sheng, column 3; or Ching Cheng Chi, column 5, as shown in table 1.

Table 1

|

2 |

4 |

6 |

8 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

g1 |

g2 |

|

匠 |

匠 |

匠 |

匠 |

商 |

商 |

商 |

重 |

重 |

|

萬 |

豐 |

平 |

王 |

王 |

郁 |

經 |

伍 |

五 |

|

全 |

年 |

正 |

壽 |

永 |

森 |

正 |

錢 |

錢 |

|

造 |

造 |

造 |

造 |

盛 |

盛 |

記 |

銀 |

銀 |

|

Engraver |

Hong |

Value |

||||||

The reverse inscriptions vary as to the characters of denomination which appear in the second and third characters of column g, which reproduces that of the one tael; and in the same column of the half-tael in which the inscriptions of columns g1 and g2 appear. Variations also are to be found in column h, where the names of the engravers appear in the second and third characters as Wan Ch'uan, column 2; Feng Nien, column 4; P'ing Cheng, column 6; or Wang Shou, column 8 of table 1. These numbers and letters are arbitrarily assigned in this study to indicate the several variations found in the inscriptions, the odd numbers being assigned to the obverses and the even numbers to the reverses. In no case are they indicative of any sequence of issue.

Nothing is known as to what has become of Wylie's specimen, although it is conceivable that it might have passed into Bushell's collection and thus be the identical coin pictured by Woodward as Type A in his "The Coins of Shanghai", wherein he stated it "is the actual one which adorned the collection of the late S. W. Bushell for many years." While Wylie's specimen does not appear to be definitely identifiable, Bushell's specimen may be easily identified by a comparison with Woodward's plate. Due to the manner in which the planchets for these coins were prepared, they frequently have small air bubbles on their surfaces which were not removed by the impact of the dies in the striking of the inscriptions. Woodward's illustration shows a group of pits below the lower right hand Chinese character of its reverse. Further, no two specimens have the outlines of the raised rims in the same relative position. By noting these features, together with the characteristic file marks near the margins, nicks and other abrasions which were present on the planchets before they were minted, one can usually determine if any particular specimen is one which has been published previously. The one tael specimen in my own collection has thus been identified definitely by such markings as the identical specimen which was sold in J. Schulman's Amsterdam auction in January 1931 (lot 1418), although I purchased it some years later from a London dealer.

One constant characteristic of the reverse die of the Type A one tael coins, present in all genuine specimens, but which does not seem to have been noted in print previously, is to be found in the lower left hand Chinese character tsao of column h. This character is customarily written with the upper right hand element composed of three strokes. However, in this instance, due to a slip of the engraver's tool, an additional stroke appears directly to the left of the center vertical stroke, just above the upper hooked stroke. From an examination of several specimens it has been noted that as the die became worn in use, this extra stroke almost fills the entire space between the two regular strokes, becoming wider and wider until in the latest strikings it almost fills the entire space between the two conventional strokes. The marginal rim of this die has an inside diameter of 37 mm.

Woodward concluded with what he termed "some degree of assurance, that not more than one die was made for each of the tael varieties, the differences in engraving marking the forgeries mentioned by Wylie." This conclusion is open to grave doubt. The examination of quite a number of specimens has caused the writer to wonder upon what basis he reached this conclusion, which does not seem to be substantiated by the evidence now available. In the collections of the late Eldon C. Keefer of Chicago and Edward Kann of Los Angeles, are two similar specimens of the Type A taels, which, although differing in many minor particulars from the norm for these coins, are most probably genuine. I do not have all of the particulars relative to Kann's specimen, which he numbers 900a in his collection and in his volume Illustrated Catalog of Chinese Coins, other than a good photograph and the plate in the book. I have examined Keefer's specimen, numbered 2 by him, and can state with assurance the following:

(a) The inside diameter of the outer rim is 38 mm and not 37 mm.

(b) The extra stroke, described above, is lacking in the last character of the reverse.

(c) It is heavier than it should be, weighing 37 grams, or 570.9 grains, instead of approximately the 565 grains average.

(d) The center dot of the obverse is not located in the same relative position to the four immediately adjacent characters, being equidistant from the ends of the nearest strokes instead of nearer the upper character to the right.

(e) None of the defects present in the Type A are present, such as the dot in the field at the left and 2 mm below and to the left of the lowest point of the 13th character of the obverse.

Summing up, although the reading of the inscriptions is the same in both coins, they were struck from different dies. The specimens appear to be made from silver of equal purity, being soft as they should be to comply with the contemporary statements that they were made from "pure unalloyed silver." If they were counterfeits they would most probably have been made from metal of inferior quality, or they would weigh more than the average. It is my considered opinion that both sets of dies from which these coins were struck were engraved by the same artisan. There are many minor points wherein the strokes making up the 32 Chinese characters differ slightly in the two sets of dies but these are only the small variations which are characteristic of two examples of the same text engraved by the same man. If the inscriptions had been copied by another individual the differences would have been greatly exaggerated.

ADDENDUM

At the foot of page 81 of Lockhart's The Medical Missionary in China , second edition, 1861, the following cryptic footnote appears: "The steel die from which these coins were made is now in the Museum at Jermyn Street." This intriguing footnote called for further investigation, for it seemed that Lockhart must have acquired the set of dies and had taken them to London when he returned to England in 1857 and had deposited them in an unnamed museum.

After the dispatch of many letters addressed to numismatic and museum periodicals and fellow collectors, both in this country and abroad, it was learned that Lockhart's note referred to the Museum of Practical Geology of the Geological Survey which was located in Jermyn Street in London since 1851, but was removed to a new building in South Kensington in 1935. However, the dies were no longer in that institution, having been transferred in 1901 to the Victoria and Albert Museum, where they are now deposited. At last the problem of their possible survival and present location is solved and we are enabled to reproduce herewith, after a full century, photographs of both original dies from which these coins were struck, through the courtesy of B. W. Robinson, Deputy Keeper of the Department of Metalwork of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

It is regretted that the grooved device for applying the reeding is not present, and no information was obtainable that would establish whether or not it ever reached England. It is believed it might have, but has since become separated from the dies during the several changes in the depositories.

Although the steel dies show some rust on their surfaces, they are otherwise in an excellent state of preservation. The photographs confirm many of the conjectures which had been made based on Lockhart's narrative and the examination of a number of specimens struck from this set of dies, especially with regard to the die defect which appears as an extra stroke in the 16th character of the reverse, as indicated by the arrow in the accompanying illustration.

The steel collar of the reverse die appears to be simply shrunk onto the square die. There is no sign of welding or riveting to secure it to the die and one can actually see daylight between the die and the collar at one or two places. The collar is in one piece, the attached ends being welded together with a diagonal joint half way along the upper side. The weld is clearly discernible from the underside.

At the center of the back of the obverse die is a large Chinese character Cheng, in an inverted position, and at the four corners are the characters Chin Sheng Li Shui (figure 2). These when read in a somewhat unconventional Chinese manner of 1: upper left, 2: lower right, 3: upper right, 4: lower left, are the 41st, 42d, 43d, and 44th characters of "The Thousand Character Classic," and are apparently here used as a serial number to identify the die. This usage of a series of characters from this, to the Chinese, universally known work, is a quite common practice, but there may be some more obscure significance in them which is not at once apparent. The above-mentioned character Cheng is repeated on the side of the collar, probably to facilitate the proper pairing of the dies when they were placed in use for striking the coins. A single character, Chin, is faintly scratched on the back of the reverse die, seemingly for the purpose of pairing it with the first character of the four-character inscription which appears on the back of the obverse die.

Figure 2 Chin Sheng Li Shui at the four corners

The utility of the vertical markings in the middle of the top and bottom recessed areas of the collar is not apparent, unless they were intended to facilitate the placing of the silver planchets in a proper position on the lower die during the process of striking the coins.

The most complete publication of the 1856 series of Shanghai coins is to be found in Edward Kann's Illustrated Catalog of Chinese Coins, published in 1954. However, several typographical errors appear to have crept into this otherwise excellent presentation, as follows: In the table at the head of page 316 are two errors in the Chinese characters. Under type D the third character should be the same as the third character in Type H; and in Type E the second character of the engraver's name should be as in Types A and H. Also on page 317 under 907 it is described in the text as being Type G, whereas the illustration under this number in Plate 131 actually depicts a Type H specimen. No Type G coin is illustrated and the specimens numbered 907 and 909 in this plate are both Type H.

The writer would be pleased to hear from any collector who possesses any of the several varieties of the taels and half taels discussed here.

Editor's Note: Originally published in The Numismatist for September 1956 and October 1956. Photographs of the obverse and the reverse dies, supplied by the Victoria and Albert Museum, appear in the second installment, but none of the actual coins were illustrated. This is arguably the most important single article written by Howard F. Bowker. It should be noted that Chu Yuan-yu (incorrectly given by Kann as Chow Yuen-yu) named on the coins was not the taotai of Shanghai, but simply the supervisor for the minting project. The acting taotai during 1855-1857 was Lan Wei[1]wen, on behalf of the real taotai, Chao Te-ch'e, who refused to take up office out of fear of rebels. An article about these coins, with an illustration (Kann 900), appeared in the North China Herald for 29 November 1856. The article confirms that the Shanghai taotai authorized the coins, and notes that the crude mint was only able to produce 3,000 coins a month. This no doubt is the source of the mintage given by Lin Guoming of 3,000 pieces for all the one tael types. However we do not know how many months the mint was in operation, so the 3,000 mintage is a minimum. Some collectors in China consider all the half tael pieces to be fantasies because there is no record of them before Woodward's 1937 article. [BWS]

19th century drawing of a primitive coining machine