Learn about the evolution of imperial portraits on Byzantine coins.

Imperial portraits were a defining feature of coins issued in the Roman Empire (27 B.C. to A.D. 476/80). After Italy fell to German soldiers late in the 5th Century, Roman civilization was to survive another thousand years in the East, securely within the walls of Constantinople. Today we know that successor empire as the Byzantine Empire, even though its inhabitants only knew themselves as Romans.

Not surprisingly, Byzantine coins retained the primary features of Roman coinage, including the imperial portrait. In this column we'll take a visual survey of how the portrait on Byzantine coins evolved over nearly a thousand years, from A.D. 491 to 1453.

Gold solidus of Anastasius I |

Copper follis of Anastasius I. |

The gold coins of the first Byzantine emperor, Anastasius I (419-518), looked almost exactly like those of his Roman predecessors. Above is one example, a gold solidus, with its typically imprecise, military portrait.

On Anastasius' bronzes, the portraits are even more crudely engraved, taking on an almost comical appearance. Their crudeness is quite appealing, and Byzantine coin collectors revel in the simplicity of these images.

Copper follis of Justinian I |

Copper half-follis of Justinian I. |

Under Justinian I (527-565) a full-facing portrait was introduced on bronzes. Shown above are two examples from the Constantinople mint: first is a follis struck in 538/9, and beneath that a half-follis struck in 542/3. The follis has a reasonably well-executed portrait, whereas the portrait on the half-follis is almost comical.

Gold solidus of Tiberius II Constantine |

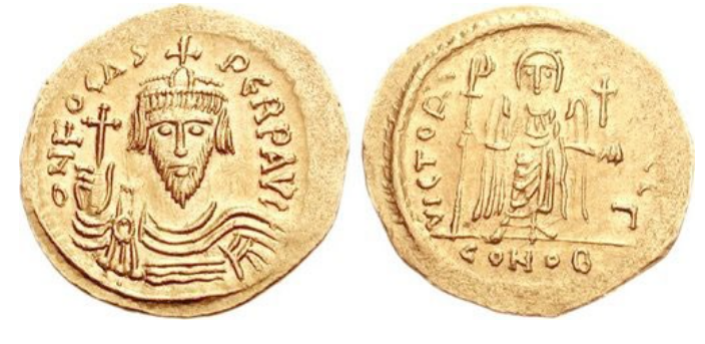

Gold solidus of Phocas |

The emperor Tiberius II Constantine (578-582) issued gold solidi with some interesting portraits, including the piece above, which shows the emperor from mid-waist. This bust type is known as a 'consular bust' because the emperor wears the garments and holds the objects associated with a consul, the highest office-holder in the senate.

Starting with Phocas (602-610) it became fashionable for emperors to portray themselves with beards. On this solidus, above, Phocas has offers a stern image.

Gold solidus of Constans II |

Gold solidus of Justinian II |

The beard fashion continued, with some emperors choosing to display extremely long beards. A perfect example is the gold solidus above, depicting the emperor Constans II (641-668).

A slightly more refined style emerges during the first reign of Justinian II (685-695). The engraving is a bit more sculptural, even if the portrait itself remains a generic representation of the emperor. Above is an example–a solidus bearing Justinian II's facing portrait.

Gold solidus of Leontius

The improved engraving style continued under other emperors, including Leontius, who revolted against Justinian II and ruled briefly from 695 to 698. Above is a gold solidus of this emperor, who came into power by rebellion and who was relieved of his authority in the same manner.

Gold solidus of Constantine V |

Gold aureus of Hadrian |

Imperial portraits on coinage became even more stylized in the 8th Century, as seen on the solidus above, issued by Constantine V (741-775), who inherited the throne from his father, Leo III. Interestingly, the deceased father is given the place of honor on the obverse of this coin, yet there is little or no effort to distinguish their appearance.

For comparison, we harken back six centuries earlier to the heyday of the Roman Empire, when Hadrian (117-138) issued coins with magnificently styled portraits. Above are a gold solidus of Constantine V and a gold aureus of Hadrian.

Gold 'globular' solidus of Theophilus |

Some of the crudest Byzantine coin portraits were issued at the Syracuse mint in the 9th Century. Above is a gold 'globular' solidus of Theophilus (829-842) struck at this important western mint. Just for entertainment value, shown below that coin is a silver tetradrachm struck at Syracuse by the tyrant Agathocles (317-289 B.C.) more than 1,100 years earlier. These two coins illustrate how, over the passage of time, there was a significant decline in artistic expression at this once-great city.

Silver tetradrachm of Agathocles

Gold histamenon nomisma of Basil II |

Electrum aspron trachy of Manuel I |

In many cases the portrait quality had improved by the 10th and 11th Centuries, as seen on this gold histamenon nomisma of Basil II (976-1025). Although they can hardly be described as lifelike, these portraits (including that of Christ on the obverse) at least have some character and some sculptural depth.

By the 12th Century it was more common for emperors to be depicted as standing figures than as portrait busts. Above is an electrum aspron trachy of Manuel I (1143- 1180) depicting on its obverse Christ enthroned and on its reverse the emperor being crowned by the Virgin Mary. As is so frequently seen on Byzantine coins, the image of the emperor is not individualized.

Gold hyperpyron of Andronicus II and Andronicus III |

Silver stavraton of John VIII |

The figures of emperors assume an even more simplistic form on this gold hyperpyron of the emperors Andronicus II and Andronicus III (1282-1328). The obverse–blurred by a poor strike–shows the Virgin Mary within the walls of Constantinople, and the reverse shows the two standing emperors crowned by Christ.

The final degradation of the Byzantine coin portrait occurred in the 15th Century, when the empire neared extinction. Shown above is a silver stavraton of John VIII (1421/5-1448) bearing on its obverse the portrait of Christ, and on its reverse that of the emperor. In both cases the images are reduced to simple sketches which, by use of a pencil, could just as easily have been created by a kindergartener as by an engraver at the Constantinople mint.