|

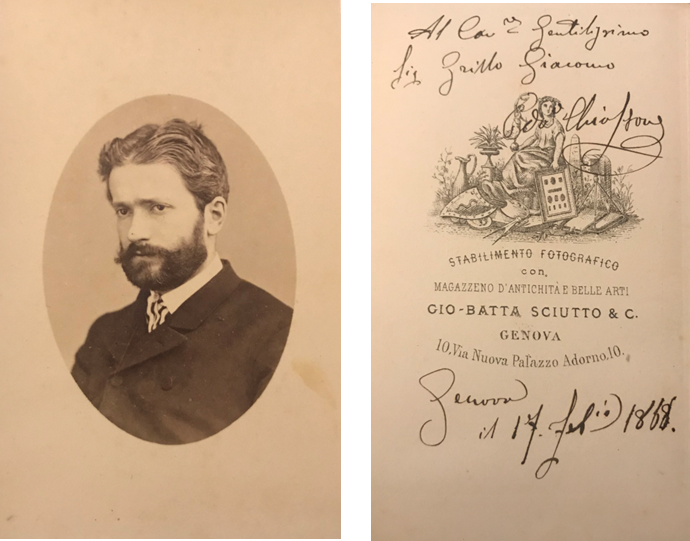

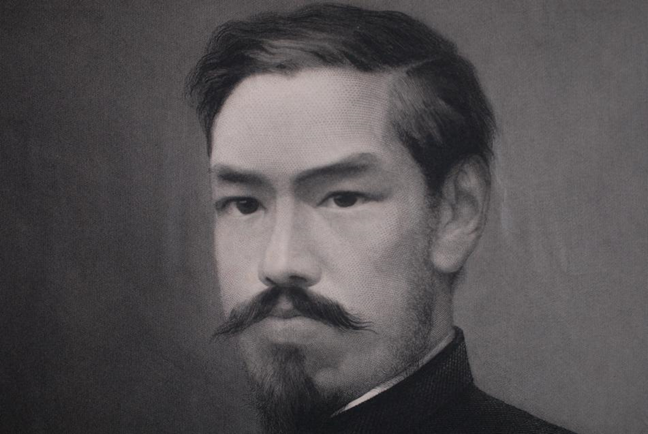

| It was customary in the second half of the 19th century to exchange photos as business cards. This recent discovery shows a photo of a young Chiossone with his original signature and a dedication to Giacomo Grillo, governor of the National Bank in the Kingdom of Italy and the first Director General of the Bank of Italy. |

It was January 14, 1875, two days after his arrival at the port of Yokohama, after a journey by sea of more than a month, when Edoardo Chiossone, a middle-aged Italian with his French interpreter Naruse Tsunekazu, entered the office of the Director of the Paper Money Bureau of the Japanese Ministry of Finance, TOKUNO Ryotsuke.

Tokuno Ryosuke was a samurai of the Satsuma domain, which along with the Choshu domain took the lead in overthrowing the Tokugawa feudal government in 1867. He had served in high positions in three ministries.

Tokuno, born in Kagoshima, was deeply devoted to the national interest, highly respected and esteemed for his great historical and literary knowledge. In 1874 he was assigned the direction of the Paper Money Bureau, and his first act, only two months into his job, was to terminate the Government's dependence on private firms for banknote and stamp printing. Rather, he hired three European specialists: Chiossone as engraver, Karl Anton Bruck as a printer, and Bruno Liebers as a typographer.

Usually, it was the norm, when employing an oyatoi gaikokujin (foreign expert) that the details of the employment contract were established with precision, but Chiossone, in the interview with director Tokuno, said that he would leave the details to the director's decision and he would do his best to train the Bureau's engravers.

Tokuno Ryosuke was a samurai of the Satsuma domain, which along with the Choshu domain took the lead in overthrowing the Tokugawa feudal government in 1867. He had served in high positions in three ministries.

Tokuno, born in Kagoshima, was deeply devoted to the national interest, highly respected and esteemed for his great historical and literary knowledge. In 1874 he was assigned the direction of the Paper Money Bureau, and his first act, only two months into his job, was to terminate the Government's dependence on private firms for banknote and stamp printing. Rather, he hired three European specialists: Chiossone as engraver, Karl Anton Bruck as a printer, and Bruno Liebers as a typographer.

Usually, it was the norm, when employing an oyatoi gaikokujin (foreign expert) that the details of the employment contract were established with precision, but Chiossone, in the interview with director Tokuno, said that he would leave the details to the director's decision and he would do his best to train the Bureau's engravers.

|

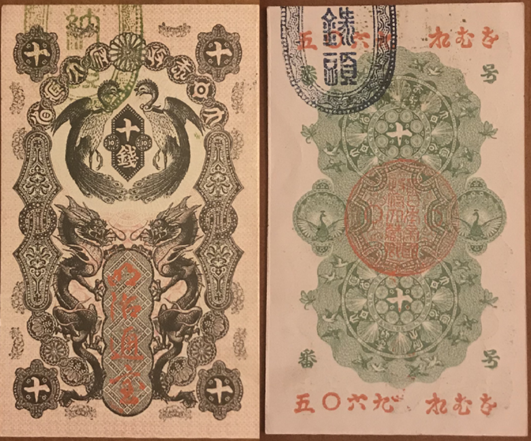

| 10 Sen banknote (Pick 1) issued by Dondorf & Nauman on behalf of the Japanese government, designed by Chiossone |

|

|

|

|

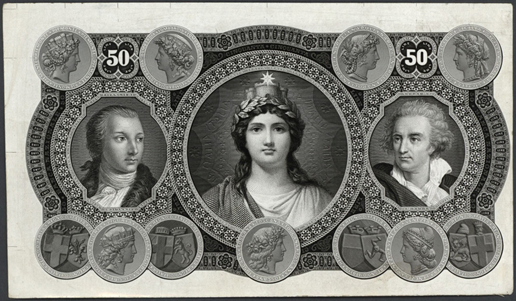

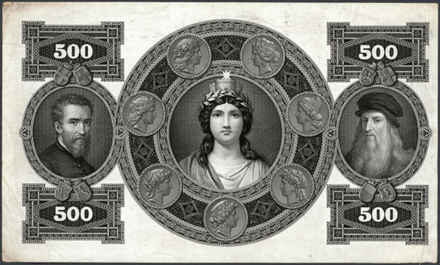

| Another recent discovery are these original proof of banknote designs for the Bank in the Kingdom of Italy executed at Dondorf & Nauman with figures of Italy, Andrea Doria, Machiavelli, Raphael, Bellini, Michelangelo, Leonardo, Gaetano Filangieri, and Vittorio Alfieri. Certainly the work of Chiossone who wished to see his designs on the emerging Italian banknotes. |

|

This behavior attracted the admiration of Tokuno and the various officials of the Bureau. In fact, from the Japanese perspective, creating a relationship of trust goes beyond a written contract and the attitude of Chiossone created from the very first moment sympathy and trust.

Tokuno was particularly in favor of the introduction of new machinery and modern techniques. For this reason Chiossone, although a foreigner could not obtain such an official title, at the age of just 43 became the head of the Paper Money Bureau, managing the modernization policies of production, and setting the path for the creation of the current National Printing Bureau.

Many of Chiossone's students became famous both in government departments and in private companies. His students were among the founders of one of today's largest global printing companies with 169 branches around the world: Toppan Printing Co., a firm that today ranges from the health care and science industries, to education and cultural exchanges, urban space and mobility, energy, and food resources. Chiossone himself had a hand in supporting Toppan.

Chiossone instructed the Japanese on the most modern printing techniques of the time, still unknown in Japan. He designed bonds, paper money, and stamps; he taught the art of western printing; how to make paper with watermarks; and importantly, how to make multiple plates from a master plate.

|

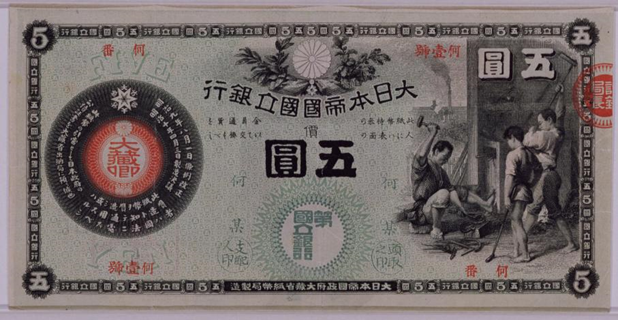

| Proof of 5 Yen banknote (Pick 21). The vignette depicting three blacksmiths at work represents one of the policies of the Japanese government: encouragement of industry. In the background the addition of Printing Bureau building suggested by Tokuno Ryosuke with the phoenix and a smoking chimney |

He effectively created an engraver's school inside the Bureau, and for sixteen years all the banknotes issued in Japan were produced under his direction. Even today, at the Japan National Printing Bureau, admiration for this Italian gentleman among Japanese workers in the sector remains high, and he is considered the father of Japanese paper money.

But let's start from the beginning. Edoardo Chiossone was born in Arenzano in Liguria, Italy in 1833.

He made his first studies in Genoa at the school of Don Pessini, a well-known institute at that time, where his cousin David Chiossone was also a pupil.

Following in the footsteps of another cousin, Domenico Chiossone, a famous copper engraver in Florence, Edoardo enrolled at the Accademia Ligustica of Fine Arts in Genoa, where he learned the basics of drawing and engraving from Raffaele Granara. The Academy, founded in 1751, was a prestigious institute where painting, sculpture, and engraving were taught. The talent shown by Chiossone in the engraving field was already visible while attending school, and he often earned awards for his excellent results.

At the age of 22 he finished his studies and entered the workshop of Granara, making progress in the reproduction of works by intaglio printing. In a collection of works of the best students of the Academy entitled Prints of the Accademia Ligustica of Fine Arts, we can find three works by Chiossone: "Giotto and Cimabue," "The violin player," and "Bread and tears." At the age of 29 he was made an honorary member of the Brera Academy of Milan. In addition to being an expert engraver, he also specialized in drawing, making very realistic portraits and combining it all with his technique and skill as an engraver. In 1867 he won a silver medal at the International Exposition in Paris.

He was hired as an engraver for the new National Bank in the Kingdom of Italy, established after the unification of Italy, and was posted to Dondorf & Naumann in Frankfurt, Germany to specialize in the latest techniques for carving and engraving plates. The desire of Chiossone was to become the engraver of the figures to be placed on the Italian banknotes once the new Printing Bureau would have been created.

Between 1870 and 1872, the Japanese government commissioned the production of nine different denominations of government notes at Dondorf & Naumann; it was the largest order received in the company's history.

The design and creation of these notes was assigned to Chiossone. His are the drawings and engravings of dragons and phoenixes on Japanese bank notes of 1872, issued on behalf of the Japanese Ministry of Finance with the values of 10 and 20 Sen, 1/2 yen, 1, 2, 5, 10, 50, and 100 Yen. Known in Japan as German shihei (German banknotes), the notes are in a vertical format and differ in color but with common motifs, showing a dragon and a phoenix reflected symbolizing the Emperor's absolute authority, established by the Meiji Restoration, replacing the Tokugawa Shogunate Government. Therefore, the initial stage of Japanese paper money was designed with dragons. Since the long journey by sea was very risky, the banknotes were printed in Germany and completed in Japan where, on the back, the bank's seal and the serial number were affixed.

With the end of the order in 1874, the plates were sent to Tokyo together with Japanese technicians trained in Germany and the production of these notes continued in Japan. To date, no method has yet been identified to differentiate banknotes produced in Germany from those produced in Japan.

In 1876, the Printing Bureau Workshop was constructed in Tokyo's Otemachi district, near the Emperor's Palace, in a then-modern, secure brickwork building. A large stone phoenix (called hōō in Japanese), about two meters high, was placed on the roof of the building. Unfortunately, the structure was destroyed by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, leading to the relocation of the plant to Tokyo's Oji District. However, the restored stone figure still stands inside the factory, and today, a stylized phoenix serves as the official symbol of the Japan Printing Bureau.

After the experience of the 1872 issue for the Japanese government, Chiossone prepared various drawings thinking that they could be used by the National Bank in the Kingdom of Italy. He recorded the figures of Columbus, Leonardo, and "Italia," as well as a design for a 1,000 lire banknote. A recent find of prototypes of intaglio notes produced at Dondorf & Naumann confirms his activities intended for use on Italian banknotes.

Unfortunately, the relationship between the National Bank in the Kingdom of Italy and Dondorf became complicated, creating a disappointment for Chiossone, who decided to leave Dondorf to go to De La Rue in London. In London he was contacted by the Japanese government with an offer of an expert's position for the Meiji Government.

This was an important historical moment for Japan, and the Japanese government spared no expense to quickly develop knowledge of new technologies.

Chiossone was offered a trip to Japan in first class, a house, and a monthly salary of 450 yen. Considering that the average annual salary of an employee was 160 yen, we can understand how attractive the offer was.

The Meiji restoration, effectively the Meiji revolution, grew out of a series of political, social and economic changes that caused the downfall of the Tokugawa shogunate and the creation of a unitary state of a modern type, through the return of governmental powers from the shogun to the emperor. The young emperor Mutsuhito, who took the reign title "Meiji," became the first emperor in several centuries with political powers.

The Meiji Period ("the period of the enlightened realm"), which went from January 1, 1868 to July 30, 1912, encompassed all but the earliest weeks of the 44 year reign of Emperor Mutsuhito, who began to change the political, social, and economic structure of Japan based on western models. It is in this area of politics and social developments that Chiossone was involved in working for the Paper Money Bureau of the Japanese Ministry of Finance, which built the finance of the country from its foundations.

The government immediately realized that the various securities, not just the banknotes, should be under the direct control of the Paper Money Bureau, which had absorbed the Printed Document Bureau in 1875. The addition of bonds, revenue stamps, postage stamps, and other certificates to the Bureau's responsibilities created a huge commitment of work. Chiossone was very busy and at times, as delivery deadlines approached, he gave up his holidays and worked on Sundays, while on weekdays he maintained a phenomenal work schedule, starting at 6:00 in the morning and finishing at 10:00 in the evening. Between 1875 and 1878, he could not even return to Italy for the death of his mother, since that was the most intense period of work. The Minister of Finance and director Tokuno were so impressed by Chiossone's dedication to work that in 1881 his salary was increased to 700 yen per month, plus an annual premium of 300 to 500 yen. In any case, Chiossone's work had already been noticed the year before, when he had received from the Meiji government the Fourth Order of Merit and the small cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun.

But let's start from the beginning. Edoardo Chiossone was born in Arenzano in Liguria, Italy in 1833.

He made his first studies in Genoa at the school of Don Pessini, a well-known institute at that time, where his cousin David Chiossone was also a pupil.

Following in the footsteps of another cousin, Domenico Chiossone, a famous copper engraver in Florence, Edoardo enrolled at the Accademia Ligustica of Fine Arts in Genoa, where he learned the basics of drawing and engraving from Raffaele Granara. The Academy, founded in 1751, was a prestigious institute where painting, sculpture, and engraving were taught. The talent shown by Chiossone in the engraving field was already visible while attending school, and he often earned awards for his excellent results.

At the age of 22 he finished his studies and entered the workshop of Granara, making progress in the reproduction of works by intaglio printing. In a collection of works of the best students of the Academy entitled Prints of the Accademia Ligustica of Fine Arts, we can find three works by Chiossone: "Giotto and Cimabue," "The violin player," and "Bread and tears." At the age of 29 he was made an honorary member of the Brera Academy of Milan. In addition to being an expert engraver, he also specialized in drawing, making very realistic portraits and combining it all with his technique and skill as an engraver. In 1867 he won a silver medal at the International Exposition in Paris.

He was hired as an engraver for the new National Bank in the Kingdom of Italy, established after the unification of Italy, and was posted to Dondorf & Naumann in Frankfurt, Germany to specialize in the latest techniques for carving and engraving plates. The desire of Chiossone was to become the engraver of the figures to be placed on the Italian banknotes once the new Printing Bureau would have been created.

Between 1870 and 1872, the Japanese government commissioned the production of nine different denominations of government notes at Dondorf & Naumann; it was the largest order received in the company's history.

The design and creation of these notes was assigned to Chiossone. His are the drawings and engravings of dragons and phoenixes on Japanese bank notes of 1872, issued on behalf of the Japanese Ministry of Finance with the values of 10 and 20 Sen, 1/2 yen, 1, 2, 5, 10, 50, and 100 Yen. Known in Japan as German shihei (German banknotes), the notes are in a vertical format and differ in color but with common motifs, showing a dragon and a phoenix reflected symbolizing the Emperor's absolute authority, established by the Meiji Restoration, replacing the Tokugawa Shogunate Government. Therefore, the initial stage of Japanese paper money was designed with dragons. Since the long journey by sea was very risky, the banknotes were printed in Germany and completed in Japan where, on the back, the bank's seal and the serial number were affixed.

With the end of the order in 1874, the plates were sent to Tokyo together with Japanese technicians trained in Germany and the production of these notes continued in Japan. To date, no method has yet been identified to differentiate banknotes produced in Germany from those produced in Japan.

In 1876, the Printing Bureau Workshop was constructed in Tokyo's Otemachi district, near the Emperor's Palace, in a then-modern, secure brickwork building. A large stone phoenix (called hōō in Japanese), about two meters high, was placed on the roof of the building. Unfortunately, the structure was destroyed by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, leading to the relocation of the plant to Tokyo's Oji District. However, the restored stone figure still stands inside the factory, and today, a stylized phoenix serves as the official symbol of the Japan Printing Bureau.

After the experience of the 1872 issue for the Japanese government, Chiossone prepared various drawings thinking that they could be used by the National Bank in the Kingdom of Italy. He recorded the figures of Columbus, Leonardo, and "Italia," as well as a design for a 1,000 lire banknote. A recent find of prototypes of intaglio notes produced at Dondorf & Naumann confirms his activities intended for use on Italian banknotes.

Unfortunately, the relationship between the National Bank in the Kingdom of Italy and Dondorf became complicated, creating a disappointment for Chiossone, who decided to leave Dondorf to go to De La Rue in London. In London he was contacted by the Japanese government with an offer of an expert's position for the Meiji Government.

This was an important historical moment for Japan, and the Japanese government spared no expense to quickly develop knowledge of new technologies.

Chiossone was offered a trip to Japan in first class, a house, and a monthly salary of 450 yen. Considering that the average annual salary of an employee was 160 yen, we can understand how attractive the offer was.

The Meiji restoration, effectively the Meiji revolution, grew out of a series of political, social and economic changes that caused the downfall of the Tokugawa shogunate and the creation of a unitary state of a modern type, through the return of governmental powers from the shogun to the emperor. The young emperor Mutsuhito, who took the reign title "Meiji," became the first emperor in several centuries with political powers.

The Meiji Period ("the period of the enlightened realm"), which went from January 1, 1868 to July 30, 1912, encompassed all but the earliest weeks of the 44 year reign of Emperor Mutsuhito, who began to change the political, social, and economic structure of Japan based on western models. It is in this area of politics and social developments that Chiossone was involved in working for the Paper Money Bureau of the Japanese Ministry of Finance, which built the finance of the country from its foundations.

The government immediately realized that the various securities, not just the banknotes, should be under the direct control of the Paper Money Bureau, which had absorbed the Printed Document Bureau in 1875. The addition of bonds, revenue stamps, postage stamps, and other certificates to the Bureau's responsibilities created a huge commitment of work. Chiossone was very busy and at times, as delivery deadlines approached, he gave up his holidays and worked on Sundays, while on weekdays he maintained a phenomenal work schedule, starting at 6:00 in the morning and finishing at 10:00 in the evening. Between 1875 and 1878, he could not even return to Italy for the death of his mother, since that was the most intense period of work. The Minister of Finance and director Tokuno were so impressed by Chiossone's dedication to work that in 1881 his salary was increased to 700 yen per month, plus an annual premium of 300 to 500 yen. In any case, Chiossone's work had already been noticed the year before, when he had received from the Meiji government the Fourth Order of Merit and the small cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun.

|

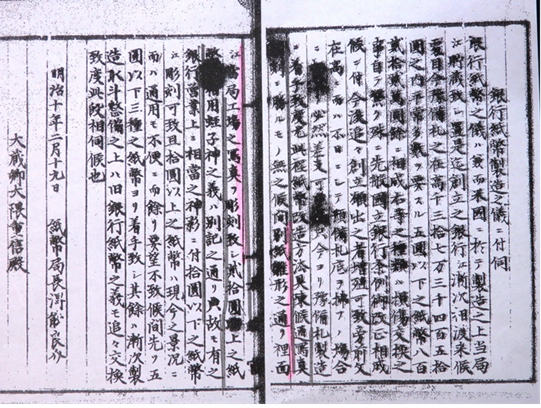

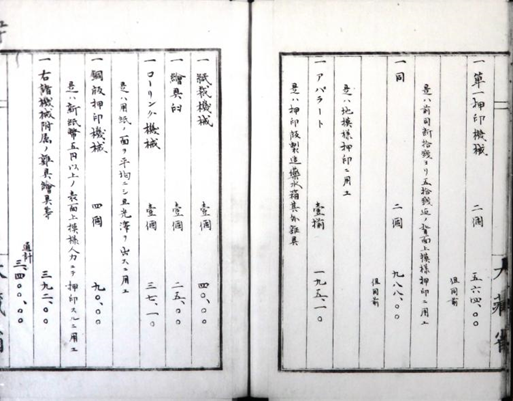

| A document dated February 19th, 1877, from Tokuno Ryosuke, Director of the Paper Money Bureau, to Okuma Shigenobu, Minister of Finance, suggesting the importance of incorporating design engraving in the banknote to prevent counterfeiting, along with the suggestion to include the Paper Money Printing Bureau building on the 5 yen banknote (Pick 21) |

|

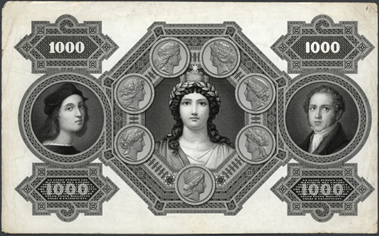

| The legendary Empress Jingu on the 10 Yen banknote (Pick 19). Third portrait in the series and the first Japanese banknote with a human portrait |

In 1871 the unification of Germany and the establishment of the German Empire were accompanied by a new German common currency, the mark. Production of banknotes transferred to the Reichsdruckerei, a public institution for the production of stamps, banknotes, and legal papers officially founded on July 6, 1879 in Berlin. The large orders received by Dondorf & Naumann were canceled and the firm had to sell 17 presses and accept the transfer of three specialists to Japan. Dondorf und Naumann must have predicted that they would lose their banknote printing business from German local State banks. During the discussion for the Japanese banknote printing order, a promise was made that should Japan decide to print its own paper money, they would provide engineers and printing presses. The transfer of technology and experience, under Chiossone's guidance, formed the basis for the expansion of banknote printing in Japan.

With the arrival of foreign experts, Japanese artists who had produced banknotes with the technique of etching were laid off. Chiossone was left as the only person truly able to produce steel-engraved vignettes for banknotes and certificates. The Japanese engravers had no experience in three-dimensional drawing of figures, and acquiring this specialization in a short time was practically impossible. Chiossone had specialized in this field during long years of apprenticeship. In just two years, the Paper Money Bureau became the first in the East. On November 17, 1877, Tokuno and Chiossone escorted Emperor Meiji for a visit to the Bureau. The Emperor was so positively impressed that eleven days later his wife, Empress Haruko, and her mother, Empress Asako, also went for a visit.

The first banknote produced entirely in Japan was created in 1877. It is a very important event that marks the ability of Japan to produce its own banknotes autonomously, without resorting to the help of other foreign powers. The note is the one-yen denomination of the second series of National Bank notes, known as the "sailor's note" for the vignette of the two sailors at the helm looking to the horizon and symbolizing one of the government's policies: a strong military.

A five-yen banknote followed in 1878, featuring a vignette depicting two blacksmiths at work with a third observing, set against the backdrop of the Printing Bureau. Another government policy aimed to encourage industry. On 10 December 1878, the Paper Money Bureau was renamed the Printing Bureau. Particularly for this banknote, we know that Tokuno suggested to his superior the importance of a complicated intaglio design to combat counterfeiters. His suggestion included incorporating into the design the Printing Bureau, which is visible in the background with the phoenix and a smoking chimney.

In 1881, Chiossone produced the first Japanese banknote with a full-face portrait. The one-yen note carries an effigy of the legendary Empress Jingu, heroine of an alleged invasion of Korea in the third century. Working from ukiyo-e prints (Japanese artistic wood-block prints), various paintings, and sketches of many beautiful girls who worked at the Bureau, he managed to trace a noble figure. The five- and ten-yen notes followed in July 1882 and September 1883. In these three notes, there are three slightly different portraits of the Empress Jingu. The portrait in the ten-yen has more realistic Japanese features than the first banknotes, where the shape of the eyes and the long nose make her look more like a foreign woman. This series of three notes was officially called kaizo shihei (improved banknotes). They were noted for their durability and other merits, such as the portrait that made counterfeiting more difficult, and the paper being produced from a special plant called "mitsumata" (oriental paper bush), which was utilized by traditional private paper mills in Japan for making security paper. This mitsumata paper was very strong, with a smooth surface good for printing, especially suitable for security paper like banknotes. It was also excellent for watermarking, contributing to its effectiveness against counterfeiting, and would be used for producing banknotes for many years to come.

Over a century passed before the Japanese would see another woman on a Japanese banknote. The 2,000 Yen Okinawa commemorative issued in the year 2000 depicted Murasaki Shikibu, a courtesan and novelist who lived more than 1,000 years earlier.

In 1885 the new Bank of Japan was born, and it was necessary to create notes of that institution (the previous notes had all been treasury notes). The Daikoku banknotes, as they are familiarly known because they show the figure of Daikokuten, god of wealth, were issued in denominations of one, five, ten, and one hundred yen. The five-yen note shows the figure of Daikokuten on the back. All of the Daikoku vignettes include rats or mice in the scene, signifying household wealth (plentiful food). The Bank of Japan took additional precautions to discourage counterfeiters, using a light blue ink difficult to photograph and using flour extracted from the konnyaku (devil's tongue) plant to strengthen the paper. Unfortunately, there were some real problems with this strategy. The lead in the blue ink reacted with the hydrogen sulphide present in onsen (hot springs), popular spas in Japan, and became black. The flour of konnyaku turned out to be very much appreciated by insects and mice.

A new government directive, in 1887, specified that only the figures of seven people indicated by the government could be shown on bank notes: Takeuchi no Sukune, Sugawara Michizane, Wake no Kiyomaro, Fujiwara Kamatari, Shotoku Taishi, Yamato Takeru no Mikoto, and Sakanoe no Tamuramaro (who never appeared on a note). These were all historical figures who had shown loyalty and support for the various imperial courts. These portraits were all executed by Chiossone, and they continued to be used long after his death.

Several of his contemporaries served (presumably unknowingly) as models. A Shinto priest of the Kanda Myojin temple (not far from the Bureau) would be the model for the portrait of Takenouchi no Sukune on the one-yen. Various portraits were available of Sugawara Michizane, protector of culture, for the five-yen. Minister Kido Takayoshi became Wake no Kiyomaro for the ten-yen note. Finally, the then-Finance Minister Matsukata Masayoshi provided the inspiration for the portrait of Fujiwara Kamatari on the one hundred-yen note. This banknote would be the last one produced by Chiossone who, in 1891, five days after completing the plates, retired after having worked for 16 years at the Printing Bureau.

Chiossone was also a great art collector. At his death he left about 15,000 objects to his alma mater, the Ligustica Academy of Fine Arts of Genoa. Its collection is today the Museum of Oriental Art of Genoa. Many Japanese art objects in collections of European museums are said to have belonged to his collection. Moreover, in 1879 Chiossone, was part of the group invited by the Bureau Director Tokuno to make a reconnaissance trip of the cultural assets of Japan that lasted about five months. Over 500 photographs were taken and Chiossone produced 200 drawings, then collected in a series of eight books entitled Kokka Yoho (The Lasting Fragrance of National Glory) with drawings reproduced in color lithographs and published by the Workshop between 1880 and 1883. Three other volumes entitled Ise Naiku Shinpobu (Treasures of the Inner Temple of Ise) and Shosoin Gyobutsu (The Imperial Properties of Shosoin) contain large double-page illustrations printed in chromo-lithography and photo-lithography. Many prints were also exhibited in Boston in 1883 in the Foreign Exhibition of Products, Arts, and Manufactures. The diary of this trip by Tokuno, published ten years later by his son, shows that the two, in addition to the themes linked to the intrinsic aims of the journey, had long and pleasant conversations.

The fame of Chiossone in Japan was not limited to banknotes, but also extended to portraits. In fact, it can be said that Chiossone became, de facto, the portrait painter of the Imperial Court. The official portrait of the Meiji Emperor is due to him. This is why Chiossone was popular in the court and that just before retiring he was awarded the Third Order of Merit and the third degree of the Order of the Sacred Treasure. At his death on April 11, 1898, the imperial court donated the sum of 500 yen for his funeral and many politicians and famous personalities of the time participated.

The transport of one of the Emperor's portraits designed by Chiossone, at the Yokosuka elementary school in July 1890, remained forever a historical event. In order to obtain a copy of the portrait, the district head, the mayor, the school principal, and some members of the city council presented themselves at the headquarters of the province. The Go-shin-ei, as the portrait is called by the Japanese people, was placed inside a wooden box, specially prepared and put on top of a small altar used to present offerings. The journey from Yokohama to Yokosuka took place on a ferry; on the arrival pier people crowded to welcome the portrait and to accompany it in procession along the way to the school. A group of students had a banner reading "Welcome to His most respectable image!" The chronicles of the time report that the emotion was palpable and that the elderly wept with joy at the passage of the imperial portrait. In the following days, many students from other schools presented themselves for a visit to the Go-shin-ei, because we must bear in mind that for the Japanese of the time, the emperor's portrait was the emperor himself.

Chiossone's contribution to the development of Japanese art, after the nation's opening to Western civilization, was monumental. Not only can we can call him the "father of the banknote," but the "father of Western printing techniques in Japan."

Chiossone is buried at Aoyama's foreigners' cemetery in Tokyo. On his plaque is an epigraph in Italian: "to the sacred memory of Professor Edoardo Chiossone, born in Arenzano (Italy) in 1833, died in Tokyo on 11 April 1898."

An obituary of 14 April 1898 in the Asahi Shinbun in Tokyo states: "On the 11th, Mister Chiossone, awarded the Third Order of Merit, residing in Japan, died from illness. Born in Arenzano in the province of Genoa, in Italy, an instructor who had taught in Italian public academies such as Milan, he was hired at the Printing Bureau of the Ministry of Finance in 1875, and in May 1880 he was awarded the Fourth Order of Merit, in July 1891 he obtained the Order of Third Merit. In the same month, after finishing his contract, he left the Printing Workshop and later became a consultant for the Fine Arts Association. He was 65 years old. His works include numerous engravings including the Emperor's portrait, the new banknotes, the exchange notes, the Bank of Japan convertible notes, privileged treasury bonds, convertible treasury bonds, the bonds of Nakasendo railways, the titles of the Ministry of Finance, bills of exchange, stamps, tobacco tax seals, etc. In addition to these, Chiossone has recorded many others. He was very generous in philanthropic works and on his deathbed he made a will to donate 3,000 yen for the poor in the Kojimachi neighborhood, where he had lived for a long time and donations to his servants. Yesterday the imperial court contributed 500 yen for the funeral."

There were more than 500 plates engraved by Chiossone, many of which have been lost, but his spiritual heritage has not been lost. Even today, the Italians residing in Tokyo, every year, during cherry blossom season, group themselves by his grave for a toast among compatriots and to remember this unforgettable artist who greatly contributed to the modernization of Japan.

With the arrival of foreign experts, Japanese artists who had produced banknotes with the technique of etching were laid off. Chiossone was left as the only person truly able to produce steel-engraved vignettes for banknotes and certificates. The Japanese engravers had no experience in three-dimensional drawing of figures, and acquiring this specialization in a short time was practically impossible. Chiossone had specialized in this field during long years of apprenticeship. In just two years, the Paper Money Bureau became the first in the East. On November 17, 1877, Tokuno and Chiossone escorted Emperor Meiji for a visit to the Bureau. The Emperor was so positively impressed that eleven days later his wife, Empress Haruko, and her mother, Empress Asako, also went for a visit.

The first banknote produced entirely in Japan was created in 1877. It is a very important event that marks the ability of Japan to produce its own banknotes autonomously, without resorting to the help of other foreign powers. The note is the one-yen denomination of the second series of National Bank notes, known as the "sailor's note" for the vignette of the two sailors at the helm looking to the horizon and symbolizing one of the government's policies: a strong military.

A five-yen banknote followed in 1878, featuring a vignette depicting two blacksmiths at work with a third observing, set against the backdrop of the Printing Bureau. Another government policy aimed to encourage industry. On 10 December 1878, the Paper Money Bureau was renamed the Printing Bureau. Particularly for this banknote, we know that Tokuno suggested to his superior the importance of a complicated intaglio design to combat counterfeiters. His suggestion included incorporating into the design the Printing Bureau, which is visible in the background with the phoenix and a smoking chimney.

In 1881, Chiossone produced the first Japanese banknote with a full-face portrait. The one-yen note carries an effigy of the legendary Empress Jingu, heroine of an alleged invasion of Korea in the third century. Working from ukiyo-e prints (Japanese artistic wood-block prints), various paintings, and sketches of many beautiful girls who worked at the Bureau, he managed to trace a noble figure. The five- and ten-yen notes followed in July 1882 and September 1883. In these three notes, there are three slightly different portraits of the Empress Jingu. The portrait in the ten-yen has more realistic Japanese features than the first banknotes, where the shape of the eyes and the long nose make her look more like a foreign woman. This series of three notes was officially called kaizo shihei (improved banknotes). They were noted for their durability and other merits, such as the portrait that made counterfeiting more difficult, and the paper being produced from a special plant called "mitsumata" (oriental paper bush), which was utilized by traditional private paper mills in Japan for making security paper. This mitsumata paper was very strong, with a smooth surface good for printing, especially suitable for security paper like banknotes. It was also excellent for watermarking, contributing to its effectiveness against counterfeiting, and would be used for producing banknotes for many years to come.

Over a century passed before the Japanese would see another woman on a Japanese banknote. The 2,000 Yen Okinawa commemorative issued in the year 2000 depicted Murasaki Shikibu, a courtesan and novelist who lived more than 1,000 years earlier.

In 1885 the new Bank of Japan was born, and it was necessary to create notes of that institution (the previous notes had all been treasury notes). The Daikoku banknotes, as they are familiarly known because they show the figure of Daikokuten, god of wealth, were issued in denominations of one, five, ten, and one hundred yen. The five-yen note shows the figure of Daikokuten on the back. All of the Daikoku vignettes include rats or mice in the scene, signifying household wealth (plentiful food). The Bank of Japan took additional precautions to discourage counterfeiters, using a light blue ink difficult to photograph and using flour extracted from the konnyaku (devil's tongue) plant to strengthen the paper. Unfortunately, there were some real problems with this strategy. The lead in the blue ink reacted with the hydrogen sulphide present in onsen (hot springs), popular spas in Japan, and became black. The flour of konnyaku turned out to be very much appreciated by insects and mice.

A new government directive, in 1887, specified that only the figures of seven people indicated by the government could be shown on bank notes: Takeuchi no Sukune, Sugawara Michizane, Wake no Kiyomaro, Fujiwara Kamatari, Shotoku Taishi, Yamato Takeru no Mikoto, and Sakanoe no Tamuramaro (who never appeared on a note). These were all historical figures who had shown loyalty and support for the various imperial courts. These portraits were all executed by Chiossone, and they continued to be used long after his death.

Several of his contemporaries served (presumably unknowingly) as models. A Shinto priest of the Kanda Myojin temple (not far from the Bureau) would be the model for the portrait of Takenouchi no Sukune on the one-yen. Various portraits were available of Sugawara Michizane, protector of culture, for the five-yen. Minister Kido Takayoshi became Wake no Kiyomaro for the ten-yen note. Finally, the then-Finance Minister Matsukata Masayoshi provided the inspiration for the portrait of Fujiwara Kamatari on the one hundred-yen note. This banknote would be the last one produced by Chiossone who, in 1891, five days after completing the plates, retired after having worked for 16 years at the Printing Bureau.

Chiossone was also a great art collector. At his death he left about 15,000 objects to his alma mater, the Ligustica Academy of Fine Arts of Genoa. Its collection is today the Museum of Oriental Art of Genoa. Many Japanese art objects in collections of European museums are said to have belonged to his collection. Moreover, in 1879 Chiossone, was part of the group invited by the Bureau Director Tokuno to make a reconnaissance trip of the cultural assets of Japan that lasted about five months. Over 500 photographs were taken and Chiossone produced 200 drawings, then collected in a series of eight books entitled Kokka Yoho (The Lasting Fragrance of National Glory) with drawings reproduced in color lithographs and published by the Workshop between 1880 and 1883. Three other volumes entitled Ise Naiku Shinpobu (Treasures of the Inner Temple of Ise) and Shosoin Gyobutsu (The Imperial Properties of Shosoin) contain large double-page illustrations printed in chromo-lithography and photo-lithography. Many prints were also exhibited in Boston in 1883 in the Foreign Exhibition of Products, Arts, and Manufactures. The diary of this trip by Tokuno, published ten years later by his son, shows that the two, in addition to the themes linked to the intrinsic aims of the journey, had long and pleasant conversations.

The fame of Chiossone in Japan was not limited to banknotes, but also extended to portraits. In fact, it can be said that Chiossone became, de facto, the portrait painter of the Imperial Court. The official portrait of the Meiji Emperor is due to him. This is why Chiossone was popular in the court and that just before retiring he was awarded the Third Order of Merit and the third degree of the Order of the Sacred Treasure. At his death on April 11, 1898, the imperial court donated the sum of 500 yen for his funeral and many politicians and famous personalities of the time participated.

The transport of one of the Emperor's portraits designed by Chiossone, at the Yokosuka elementary school in July 1890, remained forever a historical event. In order to obtain a copy of the portrait, the district head, the mayor, the school principal, and some members of the city council presented themselves at the headquarters of the province. The Go-shin-ei, as the portrait is called by the Japanese people, was placed inside a wooden box, specially prepared and put on top of a small altar used to present offerings. The journey from Yokohama to Yokosuka took place on a ferry; on the arrival pier people crowded to welcome the portrait and to accompany it in procession along the way to the school. A group of students had a banner reading "Welcome to His most respectable image!" The chronicles of the time report that the emotion was palpable and that the elderly wept with joy at the passage of the imperial portrait. In the following days, many students from other schools presented themselves for a visit to the Go-shin-ei, because we must bear in mind that for the Japanese of the time, the emperor's portrait was the emperor himself.

Chiossone's contribution to the development of Japanese art, after the nation's opening to Western civilization, was monumental. Not only can we can call him the "father of the banknote," but the "father of Western printing techniques in Japan."

Chiossone is buried at Aoyama's foreigners' cemetery in Tokyo. On his plaque is an epigraph in Italian: "to the sacred memory of Professor Edoardo Chiossone, born in Arenzano (Italy) in 1833, died in Tokyo on 11 April 1898."

An obituary of 14 April 1898 in the Asahi Shinbun in Tokyo states: "On the 11th, Mister Chiossone, awarded the Third Order of Merit, residing in Japan, died from illness. Born in Arenzano in the province of Genoa, in Italy, an instructor who had taught in Italian public academies such as Milan, he was hired at the Printing Bureau of the Ministry of Finance in 1875, and in May 1880 he was awarded the Fourth Order of Merit, in July 1891 he obtained the Order of Third Merit. In the same month, after finishing his contract, he left the Printing Workshop and later became a consultant for the Fine Arts Association. He was 65 years old. His works include numerous engravings including the Emperor's portrait, the new banknotes, the exchange notes, the Bank of Japan convertible notes, privileged treasury bonds, convertible treasury bonds, the bonds of Nakasendo railways, the titles of the Ministry of Finance, bills of exchange, stamps, tobacco tax seals, etc. In addition to these, Chiossone has recorded many others. He was very generous in philanthropic works and on his deathbed he made a will to donate 3,000 yen for the poor in the Kojimachi neighborhood, where he had lived for a long time and donations to his servants. Yesterday the imperial court contributed 500 yen for the funeral."

There were more than 500 plates engraved by Chiossone, many of which have been lost, but his spiritual heritage has not been lost. Even today, the Italians residing in Tokyo, every year, during cherry blossom season, group themselves by his grave for a toast among compatriots and to remember this unforgettable artist who greatly contributed to the modernization of Japan.

|

|

| The 10 Yen banknote (Pick 24) featuring the image of Daikokuten, the god of commerce |

Detail of the 5 Yen banknote (Pick 27) with the portrait of Sugawara no Michizane |

|

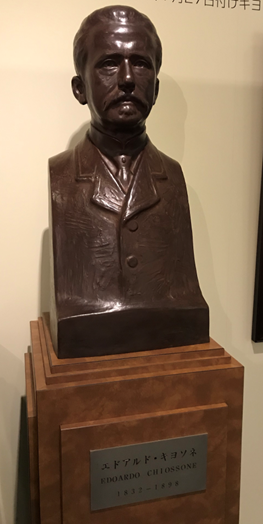

| Bust of Chiossone preserved at the Stamp and Banknote Museum of Tokyo |

|

| Detail of the portrait of Emperor Meiji executed by Chiossone without ever seeing the emperor in person. Chiossone hid among the bushes of the garden to observe and sketch the Emperor. Later, Chiossone would borrow the emperor's military uniform to wear it and make a portrait of himself in uniform. The result was highly appreciated by the Imperial Court |

|

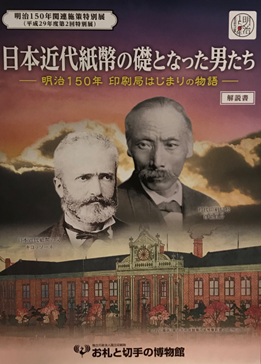

| Poster of the 2017 exhibition on the 150th anniversary of the National Printing Bureau featuring images of Edoardo Chiossone and Tokuno Ryosuke. In the small Japanese caption below Chiossone's image, it reads: "Father of modern Japanese banknotes". Visible also is the then-modern brickwork building of the National Printing Bureau |

|

|

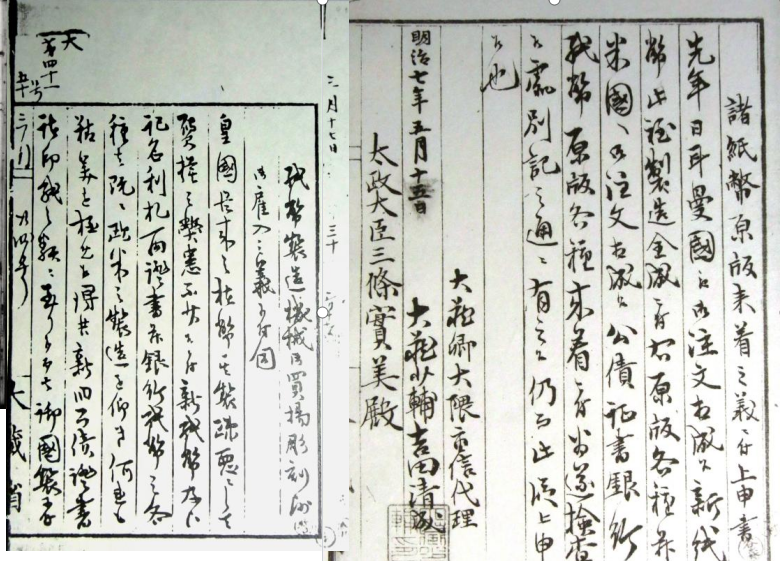

| Official documents regarding the acceptance of machinery from Dondorf und Naumann, as reported by Kyonari Yoshida, Bureau Director of Finance and deputy Minister of Finance, on May 15th, 1874, to Sanetomi Sanjo, Prime Minister. The 10-page report discusses original plates for each denomination, original Erhöht letterpress plates, cliché plates, numbering plates, and proofs for each denomination. |

|