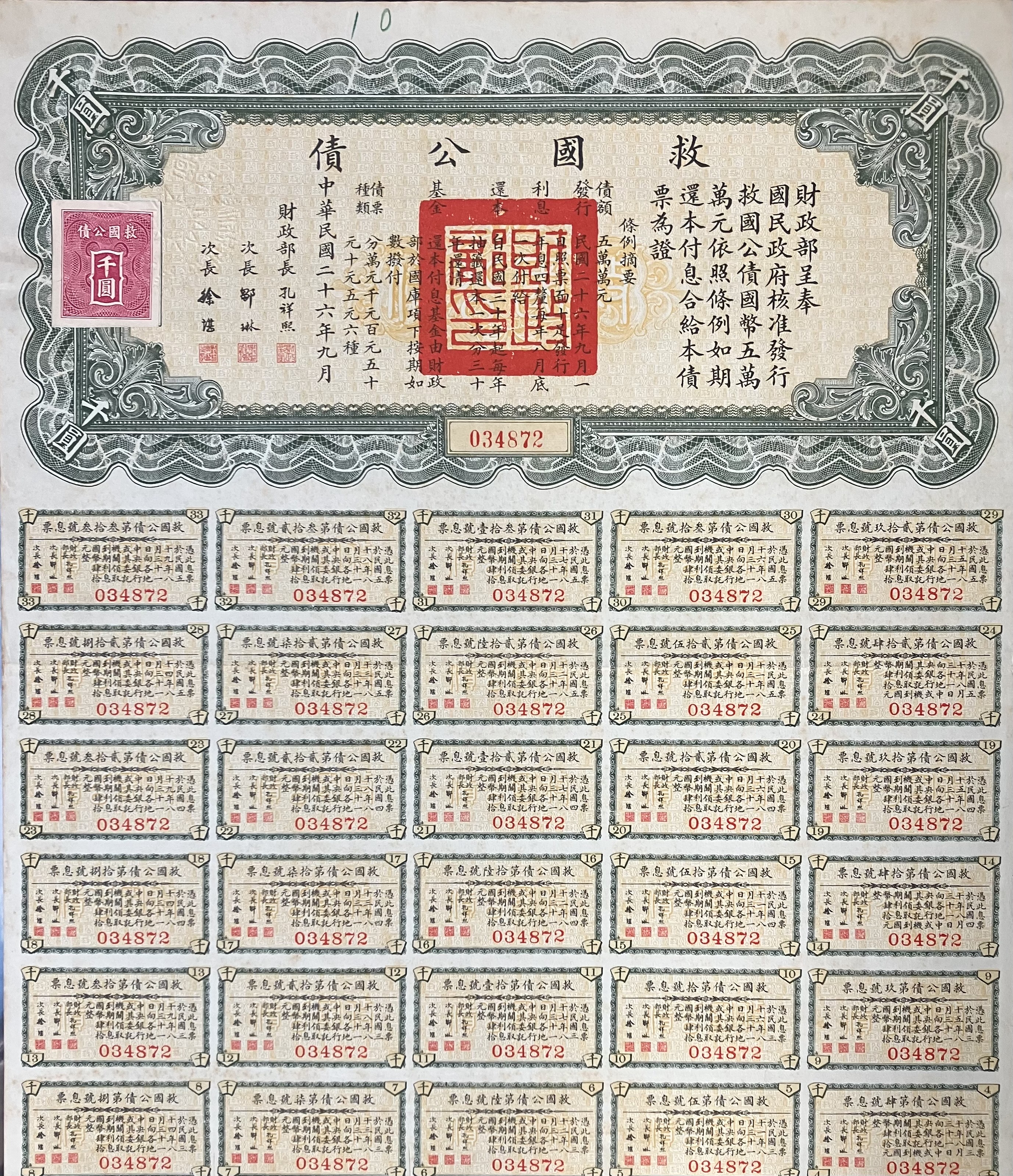

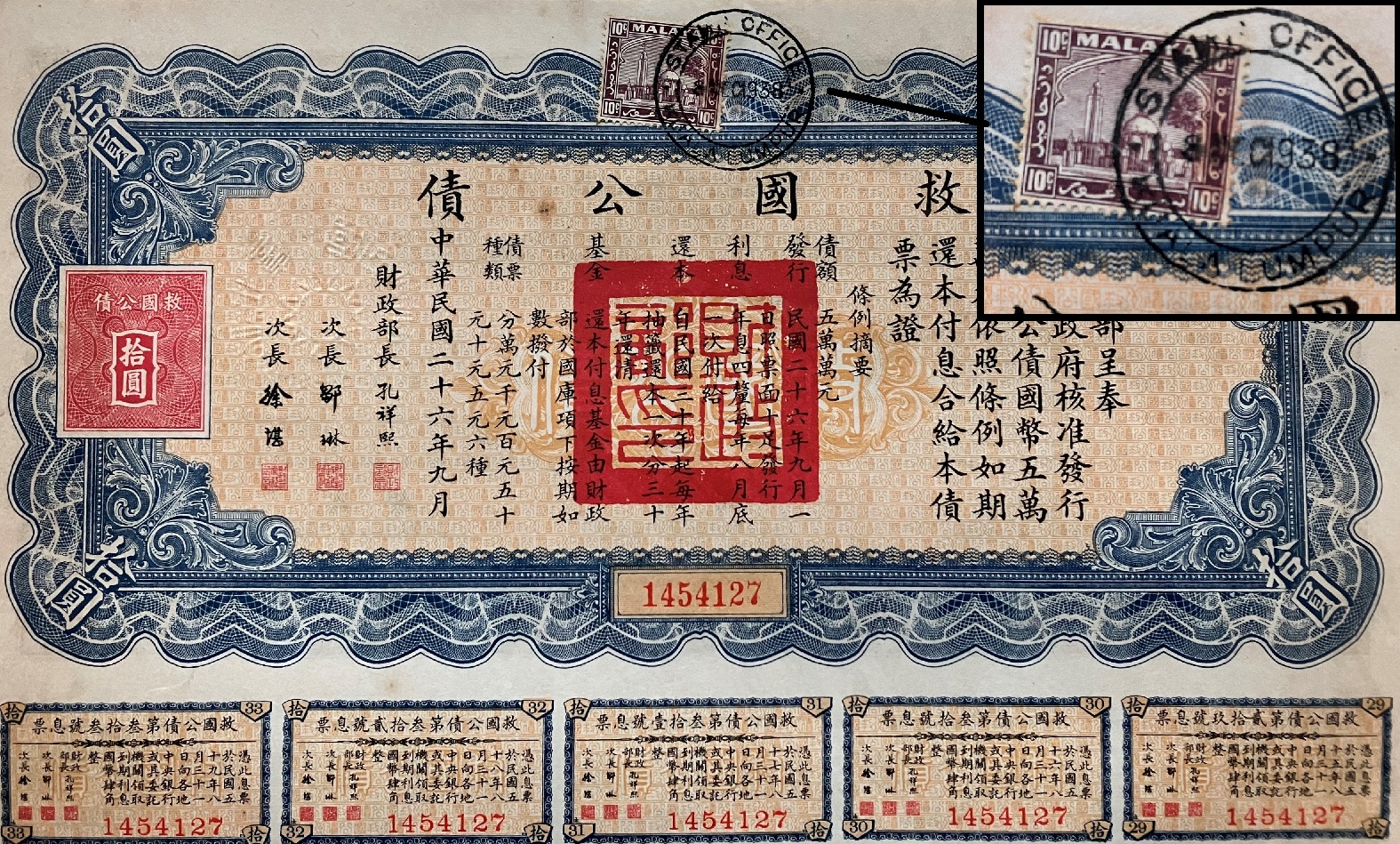

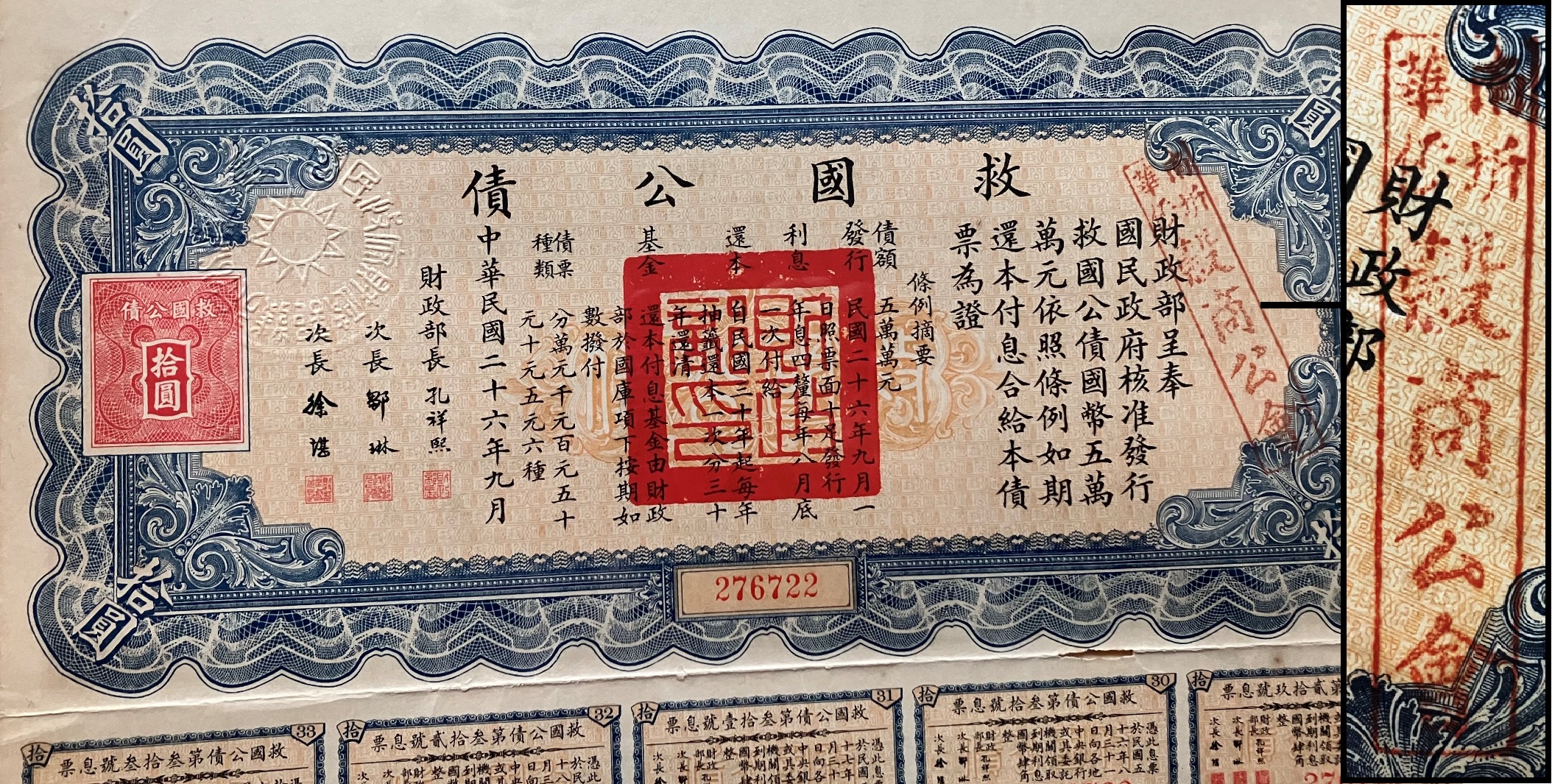

The National Salvation Bond (Fig. 1) was the first large-scale debt issued to raise funds for the Second Sino-Japanese War by the Republic of China government after the outbreak of the War of Resistance. On September 1st, 1937, the bonds were officially issued, including six face values ranging from ten thousand dollars, one thousand dollars, one hundred dollars, fifty dollars, ten dollars to five dollars, totaling five hundred million dollars. The annual interest rate was 4 %, and the principal would be repaid once a year by drawing lots in the following 30 years from 1941.1

Overseas Chinese in the Southeast Asia Purchased Bonds to Serve the Nation

Whenever China is in trouble, overseas compatriots uphold their patriotism and donate enthusiastically, even in wartime. By the end of 1937, over 220 million dollars had been raised in only four months after the issuance of the National Salvation Bond, contributing to 27% of the annual national revenue, of which a large portion came from overseas compatriots. According to statistics, some 8.7 million overseas Chinese resided in various places during the war period. About 8.36 million people who lived in Asia accounted for the majority of overseas Chinese, and as for those who lived beyond Asia, some 80,000 Chinese Americans accounted for the largest number. The overseas Chinese immediately became the target of fundraising during the Sino-Japanese War. They subscribed for more than one-third of the total, and the largest contribution was made by those who lived in British Straits Settlements.2

Despite the enthusiastic response from the overseas Chinese who were eager to donate, they did not realize that the bonds issued during the Sino-Japanese War, including the National Salvation Bond, were all domestic debts of China. Once these bonds were raised funds beyond China, there would be a series of problems such as the political attitude of the local government, financial laws, and jurisdiction. The National Salvation Bond was the first bond to be issued during the war, so it was the first to encounter problems. How to solve these problems? The destiny of the National Salvation Bond was also of great significance to other war bonds to be issued in Southeast Asia later.

Overseas Chinese in the Southeast Asia Purchased Bonds to Serve the Nation

Whenever China is in trouble, overseas compatriots uphold their patriotism and donate enthusiastically, even in wartime. By the end of 1937, over 220 million dollars had been raised in only four months after the issuance of the National Salvation Bond, contributing to 27% of the annual national revenue, of which a large portion came from overseas compatriots. According to statistics, some 8.7 million overseas Chinese resided in various places during the war period. About 8.36 million people who lived in Asia accounted for the majority of overseas Chinese, and as for those who lived beyond Asia, some 80,000 Chinese Americans accounted for the largest number. The overseas Chinese immediately became the target of fundraising during the Sino-Japanese War. They subscribed for more than one-third of the total, and the largest contribution was made by those who lived in British Straits Settlements.2

Despite the enthusiastic response from the overseas Chinese who were eager to donate, they did not realize that the bonds issued during the Sino-Japanese War, including the National Salvation Bond, were all domestic debts of China. Once these bonds were raised funds beyond China, there would be a series of problems such as the political attitude of the local government, financial laws, and jurisdiction. The National Salvation Bond was the first bond to be issued during the war, so it was the first to encounter problems. How to solve these problems? The destiny of the National Salvation Bond was also of great significance to other war bonds to be issued in Southeast Asia later.

Fig. 1 A 1000-dollar National Salvation Bond issued by the

Republic of China government in 1937 after the outbreak of the war.

Note:

1 For a detailed introduction of the National Salvation Bond, please refer to the third part of the book From Interest Borrowing and Lending to Patriotic Bonds: A Detailed Account of Early Chinese Domestic Bonds (1894-1949) by Stephen Tai, pp. 191. Business Weekly Publishing House. September 2017.

2 Stephen Tai, From Taiwan Coastal Defense Borrowing to Patriotic Bonds: Counting the Early Chinese External Bonds (1874-1949). Part II – Chapter III: The Bonds Circulating Beyond China during the War Period. pp. 191. Business Weekly Publishing House. September 2017.

Problems Faced by the National Salvation Bond

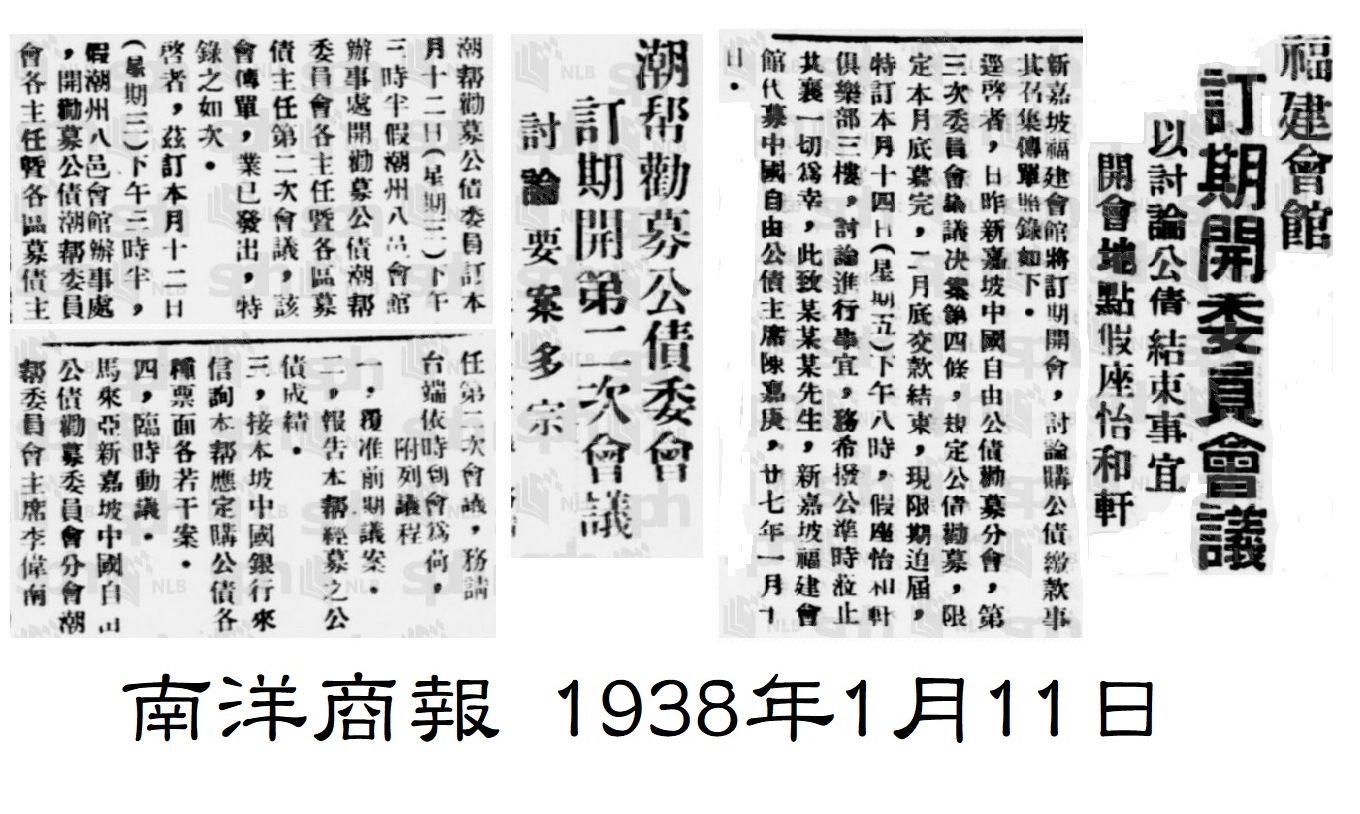

The overseas Chinese in Singapore proposed to set up a committee for raising funds through the National Salvation Bond on September 12, 1937, but it was suspended due to the jurisdiction of the local government and the objection of the British government.

After diplomatic negotiations between China and Britain, Sir Shenton Thomas, the High Commissioner of the Federated Malay States, agreed to make concessions and applied to the Colonial Office in London on an ad hoc basis. However, one of the conditions was that the British side retained the right of consent to leaders of the fundraising committee. Tan Kah Kee (陳嘉庚), Hu Wen Hu (胡文虎), Lam Mun Tin (林文田), Tan Chin Hian (陳振賢), Tan Ean Kiam (陳延謙) and other overseas Chinese leaders were selected, while some of the candidates purposed by the Chinese government were excluded from the committee. Another condition was that the bonds could only be raised from the overseas Chinese community in Singapore and Malaysia and it should not be issued to the public. Therefore, no underwriter shall be used to handle the related affairs, and the bonds could only be sold by overseas Chinese organizations.

Under these conditions, the issuance of the National Salvation Bond was finally approved on October 17th, and the sale of the bonds began to be actively carried out in various overseas Chinese communities (Fig. 2). 3

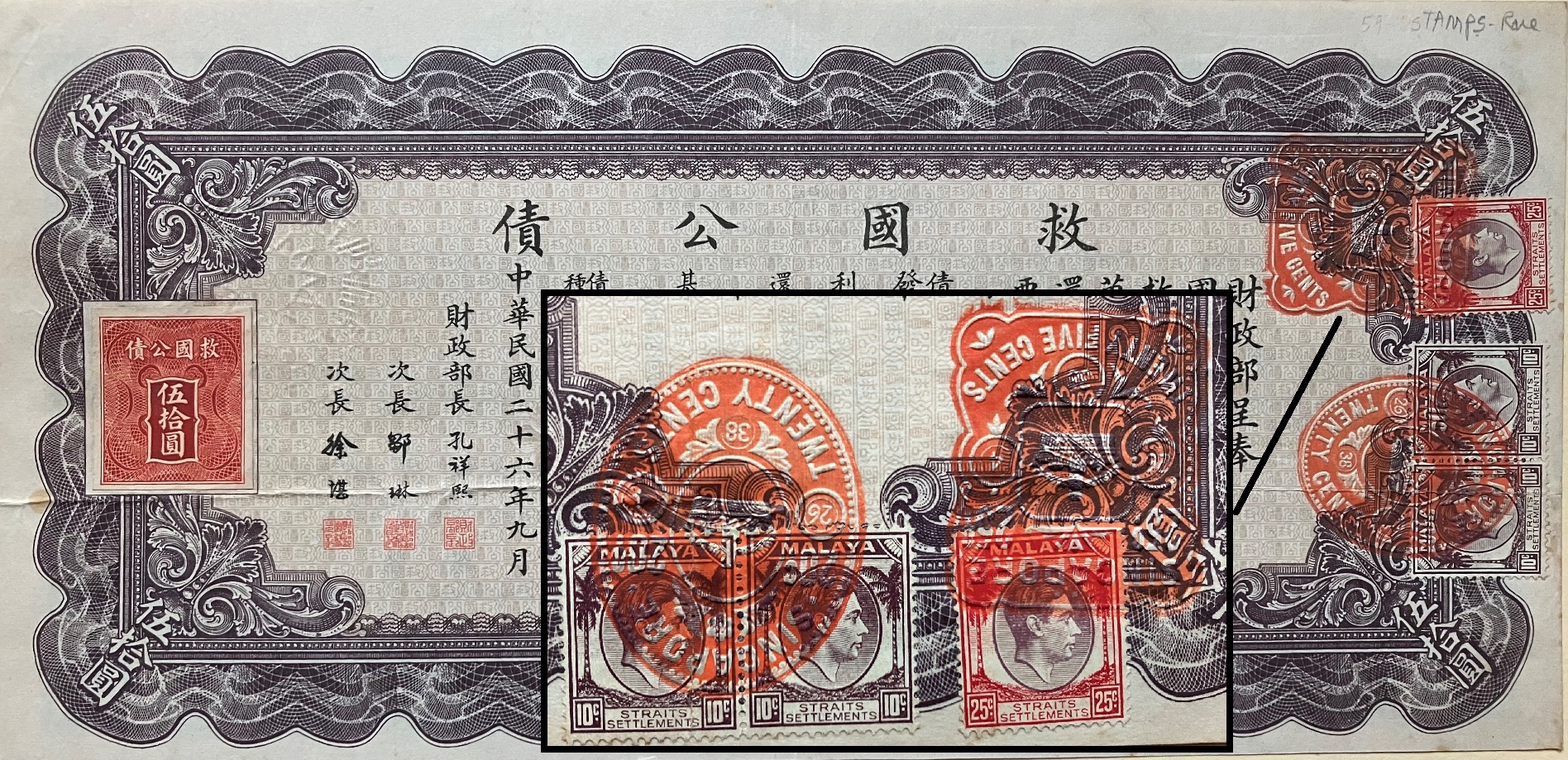

In addition, the National Salvation Bond in Singapore and Malaya was regarded by the British colonial government as a kind of security and should be subject to the same stamp duty as other securities circulating in Singapore and Malaya.

The Stamp Duty in Singapore and Malaya

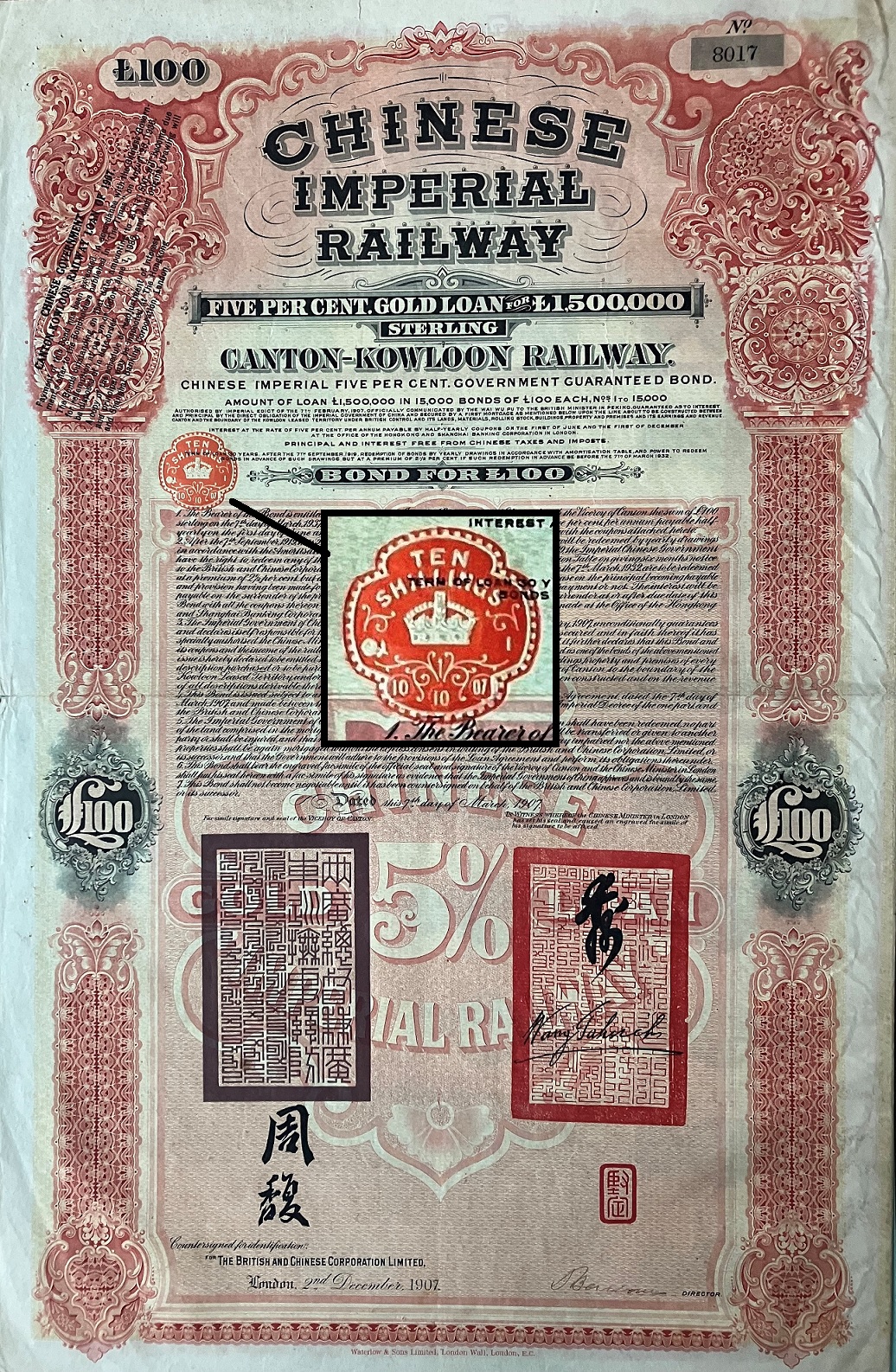

From the 17th century, European countries generally taxed all kinds of deeds and certificates of title, and such taxes became an important source of government revenue. It is called stamp duty because a stamp will be made on the certificate as proof of tax payment. In the 19th century, stamp duty was also commonly applied to stocks and bonds, and became a security transaction tax. In addition to stamping, tax stamps were later affixed to the certificate. Since the late Qing dynasty, the stamp duty had been imposed on Chinese bonds by the overseas countries where the transaction took place. For example, Fig. 3 is a 1898 Chinese Imperial Government Gold Loan. It had been transacted in Britain, France, and Holland, so it was subjected to the stamp duties by these three countries. Fig. 4 is a 1907 Chinese Imperial Canton-Kowloon Railway Gold Bond, and it was subject to stamp duty by the United Kingdom when issued in London.

As for the National Salvation Bond, although it was a kind of Chinese domestic bond, and the buyers were all overseas Chinese, local governments imposed taxes as it was transacted overseas. It was legitimate, and the Chinese side could do nothing about it. But these overseas Chinese who aspired to serve the motherland were undoubtedly heavy-laden.

According to the regulations of the British Malayan government, the standard of taxation on the National Salvation Bond was that 45 cents should be charged as the stamp duty for every 100-dollar bond, subject to a minimum sum of 100 dollars. However, the amount of duty imposed by the Stamp Office (Fig. 5) varied from time to time as seen from the existing bonds. In the case of a 50-dollar bond, 45 cents were charged in accordance with the regulations (Fig. 6). However, the practical ratio of stamp duty was chaotic. There was also a 100-dollar bond only charged for 25 cents, as well as 5-dollar and 10-dollar bonds charged for 10 cents. (Fig. 7)

3 Li Sihan, A History of the Chinese in Southeast Asia, Chapter 15, The Japanese Invasion of China and the Rescue Movement by Chinese in Southeast Asia. Wunan Book Publishing, 2003 edition.

Fig. 2 The report on the fundraising through bonds Fig. 3 A 1898 Chinese Imperial Government Gold Loan

on the Nanyang Slang Pau published on January 11, 1938 with British, French, and Dutch stamps

Fig. 4 A 1907 Chinese Imperial Canton-Kowloon Railway Gold Bond Fig. 5 Stamp Office in British Colonial Singapore

issued by the Qing government with a British stamp.

Fig. 6 A 50-dollar National Salvation Bond charged for Fig. 7 A 10-dollar National Salvation Bond charged for

45 cents by the Straits Settlement Stamp Office. 10 cents by the Straits Settlement Stamp Office. Stamped

tamped Date: April 26th, 1938. Date: December 8th, 1938.

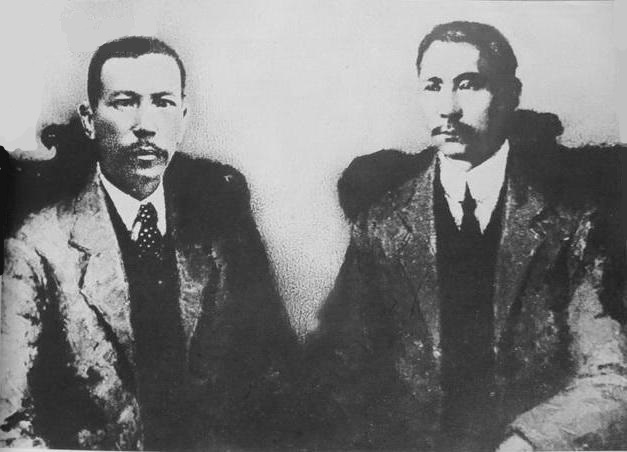

Figure 8: Singaporean overseas Chinese leader Tan Kah Kee

with Founding Father Sun Yat-sen (Source: Wikipedia)

Fig. 9 A 10-dollar National Salvation Bond stamped with the mark of

Nanqi Overseas Nan Ky Overseas Chinese Merchants Association

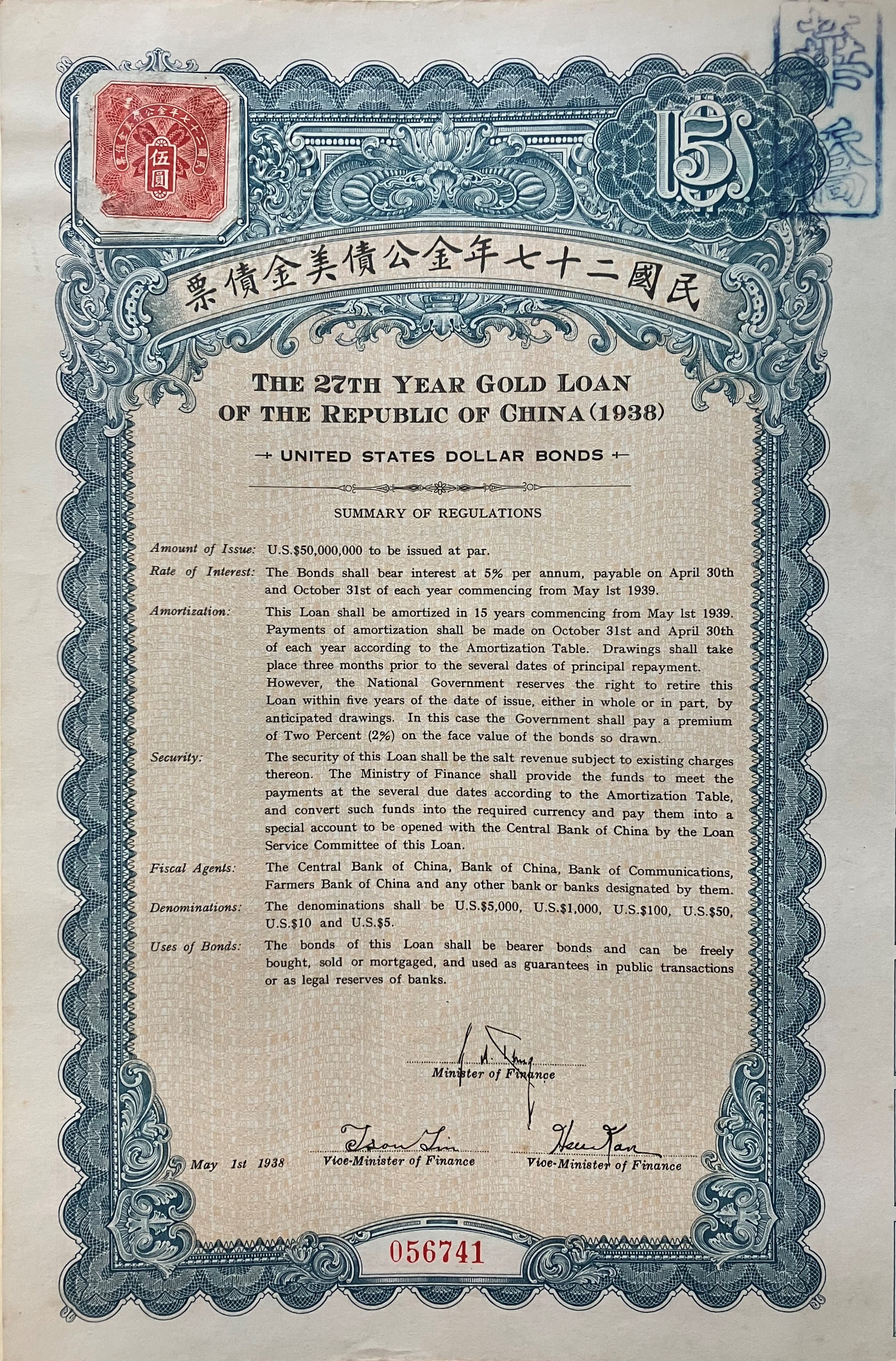

Fig. 10 A 1936 5-dollar Gold Bond stamped

with characters that mean Overseas Chinese

The Tax-Avoidance Measures Proposed by Tan Kah Kee

In order to avoid the stamp duty and reduce the cost of fundraising, the overseas Chinese leader Tan Kah Kee (Fig. 8) wrote a letter to Tse-vung Soong (宋子文) on January 24th, 1938. 4 In this letter, it was mentioned that two approaches had to be adopted to avoid the duty.

The first one is that the temporary certificates and remittances for the subscription of bonds should no longer be handled by the Chinese or overseas Chinese banks. Instead, temporary certificates should be issued by various organizations. The payment for bonds should be remitted to the mainland through the Bank of China or Relief Committee of Nanyang Overseas Chinese for China's Refugees.5

4 Overseas Chinese History on National Salvation Bond, China Art News, May 15, 2018.

5 The Relief Committee of Nanyang Overseas Chinese for China's Refugees was founded in Singapore on October 10, 1937, after the outbreak of the war of resistance against the Japanese, also known as “Nanyang Overseas Chinese Relief Committee of Nanyang Overseas Chinese for China's Refugees”. Tan Kah Kee assumed the position of the chairman.

Second, the bonds should be sent directly to the overseas Chinese who subscribed to bonds through various organizations.

Originally, the delivery and remittance of bonds were mainly undertaken by Chinese banks and overseas Chinese banks. Tan Kah Kee found that the practice was easily targeted and taxed by the Malaysian government. Therefore, it is suggested that the overseas Chinese associations in various places should take the place of these banks to remit funds back to China in the name of the overseas Chinese associations and that the bonds should be received and sent on behalf of these overseas Chinese associations, so as to avoid investigation and achieve the purpose of tax avoidance.

Tan Kah Kee's suggestion was adopted immediately. I have seen that most of the National Salvation Bond with stamps were stamped in the first half of 1938, and few bonds with stamps after that were seen; the latest one was stamped by the Kuala Lumpur Stamp Office on December 8th, 1938 (Fig. 7). It is assumed that the countermeasures suggested by Tan Kah Kee were gradually implemented and became effective in 1938. As a result, the stamp duty levied by the local government was gradually reduced, and at the end of the year, it was difficult to find a National Salvation Bond with stamps.

The Experience from Singapore and Malaya Led to the Main Mode of Fundraising by Bonds

The overseas Chinese organizations took the place of the banks in receiving payments, remitting to China, and collecting and sending bonds, which experience from Singapore and Malaya then became the main mode of the Republic of China government in the fundraising by bonds in Southeast Asia. It was not only adopted in British Malaya but also in many other countries.

In French Indochina (Vietnam), there were more than 400,000 overseas Chinese, mainly concentrated in Nam Ky, present-day southern Vietnam, and southeastern Cambodia. Saigon, present-day Ho Chi Minh City, was the capital, with about 300,000 overseas Chinese, who had established tightly-knit organizations in various industries and occupied an economic advantage. As the French colonial government tended to prohibit the National Salvation Bond, the fundraising was forced to go underground, and the overseas Chinese communities became an important base. Fig. 9 shows a 10-dollar bond collected in French Indochina at that time. The stamp of "Nan Ky Overseas Chinese Merchants Association" on the face of the bond is another example of the important role that overseas Chinese organizations play in raising funds and selling bonds.

After the National Salvation Bond, the Republic of China government issued many other bonds, such as the National Defense Bond, Gold Bond, Military Bond, Construction Bond, etc. Their issuances in Southeast Asia also took the experience from Singapore and Malaya. However, due to the difference with the domestic fundraising method, some of the bonds handled by the overseas Chinese organizations were stamped with characters “華僑” (overseas Chinese) to make differentiation (Fig. 10).

Later, due to the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the war quickly spread to Southeast Asia, and the fundraising by bonds was forced to come to an end. The fundraising by bonds finally ended at the end of January 1942 when the Malay Peninsula was occupied by the Japanese army, and on February 15, on the eve of the fall of Singapore.