The monetization of gold and silver in the Tang and Song dynasties is a frequently-explored academic topic. The increase in minerals, the improvement of refining technology, and the large number of imports from foreign countries1 are regarded as the reasons for the gold and silver monetization and became a direction of research. However, as a kind of currency in circulation, gold and silver must be valued according to their purity, yet few researchers have mentioned two major technical problems, that is, purity analysis and weight measurement.

The way to identify the purity of gold and silver in the Tang and Song dynasties

As far as we know, the most detailed information on the analysis and identification of gold and silver purity is provided by The Identification of the Counterfeited Treasure (《寶貨辨偽》) from the end of the Southern Song dynasty. 2

In the section about gold, it writes "the purity of gold can be identified through the color presented by striking the gold on the touchstone, which method can examine the purity ranging from 5% to 100%." In addition, the technique of identifying whether or not low-purity gold or silver was used or encased was also known at that time from the hammer marks and the seams on the bottom of gold bars or goldware.

As for the silver, it writes "The back of a real silver ingot is flat as paper, the center is sunk, and the four corners are concave. The way to identify the purity of silver can only be understood but not expressed. If you can use it correctly, it will be exactly precise." "The silver content of jin qi hua yin [金漆花銀] silver ingot is 100%, nong diao hua yin [濃調花銀] 99.9%, cha hua yin [茶花銀] 99.8%, da hu hua yin [大胡花銀] 99.7%, bao hua yin [薄花銀] 99.6%, bao hua xi shen [薄花細滲] 99.5%, zhi hui hua yin [紙灰花銀] 99.4%, xi shen yin [細滲銀] 99.3%, lu shen yin [麄滲銀] 99.1%, duan shen yin [斷滲銀] 98.5%, and wu shen yin [無滲銀] 97.5%. As for silverware, jewelry, and bracelets, people like those in the popular style, so they are recast frequently, which makes the purity to be lower and lower. It is especially important to be careful when identifying the gold-plated silverware." What is noteworthy is that people in the Song dynasty could not only identify the purity from the appearance of silver ingots, but the subtle differences in features and color were also the basis for judging, with only 0.1% between the two purity grades. This kind of skill is amazing. Undoubtedly, this has laid an important foundation for the monetization of silver.

People learned a little about how to distinguish silver ingots gradually. Later, especially in the Ming and Qing dynasties, the money shops and the appraisal stores gathered the relevant know-how with great success, much of which was inherited from the experience in the Song dynasty.

Though the skill to identify the purity of silver was mature in the Song dynasty, the development of the gold and silver weighing technique was relatively slow, which might be the reason for the difficulty in the gold and silver monetization. This article will explore this issue that has not been noticed.

The invention and impact of steelyard in the Song dynasty

The wide use of the scale is attributed to the circulation of silver ingot, a currency valued by weight. The scale used in ancient China is an equal-arm balance (Figure 1). However, limited by manufacturing technology, the traditional scales cannot meet the two conditions required for weighing silver ingots. First, the weight unit of the scale must be small enough to weigh the mace and candareen to cope with various prices in transactions. Second, the size of the scale must be light enough to carry around.

The steelyard was not commonly used in the Song and Yuan dynasties, so it was hard for gold and silver to circulate

However, because of the technical limitations of manufacturing, delicate steelyards for weighing micro-objects had been exclusive to the palace, while the early folk steelyard could only be used to weigh daily commodities, not suitable for precious gold and silver due to the large error margin and size. A Yuan-dynasty fresco featuring an officer weighing fish also reveals this situation (Figure 3). The Yuan was a dynasty that attached great importance to weights and measures, and the market was equipped with official scales to ensure fair trade; however, because of the immature weighing techniques, though the officer used an official steelyard, it was too big and inaccurate to weigh gold and silver but only used to measure the weight of daily objects.

The steelyard also found its way into neighboring Asian countries and even into Europe. Figure 4 shows a steelyard from England at the beginning of the 20th century, which was quite large, weighing about 1 kilogram. It weighed in pounds (453 grams), and it could weigh objects ranging from 0.1 pounds to 9 pounds. It was used for weighing goods such as fish, meat, vegetables, and fruits like the types in early China had done.

Hand steelyards became a necessity in the Ming dynasty, which allows the silver to circulate in all walks of life

In the late Ming dynasty, silver was declared legal tender, and various silver ingots were circulated in all sectors of society. This result was made by the achievement of a variety of conditions. Among them, the birth of a kind of steelyard specifically for weighing gold, silver, medicine, and other precious items was crucial.

The steelyard for weighing gold and silver is compact, and the arms and weights can be stored in a small wooden box and carried around, which is the reason why it is called a hand steelyard which means it is portable. (Figure 5)

Soon after, the hand steelyard became a handful of necessities, thus solving the long-existing problem that silver could not be weighed. As you could value silver pieces regardless of size by weighing them at any time and any place, the hand steelyard was quite popular. It was easier than ever to trade in silver, which transformation allowed silver to pass unhindered through both the public and private economies, fully performing its monetary function.

In the late Ming dynasty, local silver ingots sprang up all over the country. These small silver ingots of various shapes and sizes are mostly less than 10 taels or even 1 tael, and a large number of silver pieces at the weight of less than one mace were circulating on the market6. The hand steelyards were designed in response to the silver in actual circulation at the time. There were all kinds of hand steelyards that could weigh items lighter than 10 taels, and even mace and candareens (figure 6).7 Some of these steelyards are illustrated below. ((figure 7-11)

The hand steelyard did not fade out of the market with the silver ingots but continued to be used for weighing silver dollars

In addition to silver ingots, silver dollars flowed into China starting from the late Ming dynasty and became very popular in the Qing dynasty. Later, the Chinese silver dollars were also put into circulation. Although the weight of these vintage coins was consistent when they were minted, their weight was always reduced due to the prevalence of filing and chopping on silver coins. Therefore, the value of the circulating coins must be decided after weighing.8 Thus, hand steelyards were not only used for weighing silver but later had more applications in the process and transactions of silver dollars.

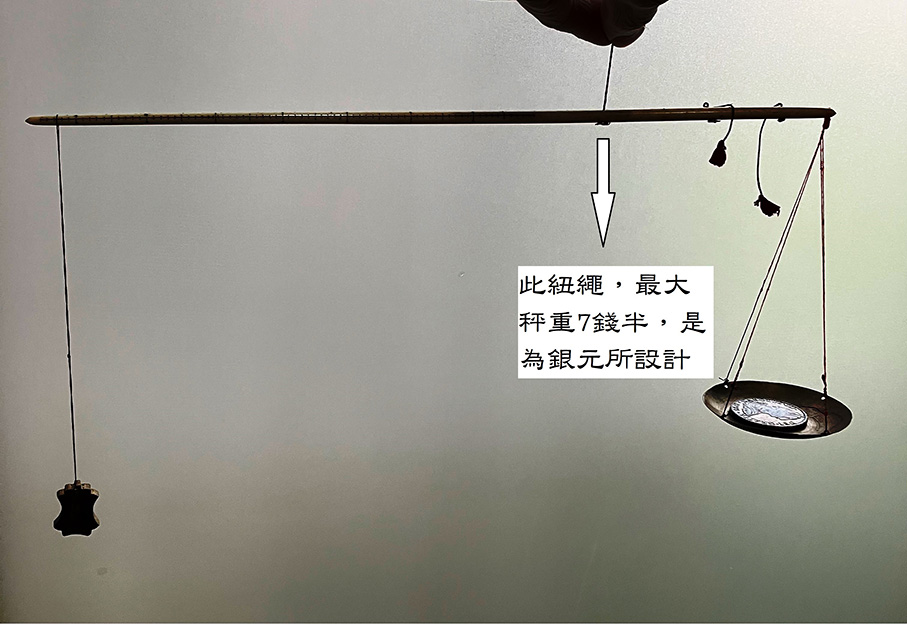

Although both silver dollars and small silver pieces can be weighted with the same hand steelyards, exclusive designs for silver dollars can still be found on some hand steelyards. The Steelyard 5 shown in Figure 11 is an example. This hand steelyard presumed to date from the late Qing dynasty was made by Anlan Money Shop in Guangzhou. At that time, Guangzhou mainly used silver dollars, while silver ingots were rarely used, so the design of hand steelyards took into account the weighing target of silver dollars as the priority rather than the silver ingots. For this reason, the smallest weight scale among the three pivots of the hand steelyard, with an upper limit of 7.5 mace, can be said to be designed specifically for silver coins. One silver dollar weighs about 7.2 mace, so the pivot can be used as long as it is a silver dollar or a factional silver coin, without the trouble of changing the pivots in the process of weighing (Figure 12). As for the other pivots, the upper limit of the weight range is 3.6 taels and 11 taels respectively, which is about the weight of 5 and 15 silver dollars respectively. In addition, at the end of the Qing dynasty, Guangdong still minted local square trough sycees, with a unit weight of about 10 taels,9 which could also be weighed by this kind of hand steelyard.

Figure 7 [Steelyard 1] It has two pivots, with a weighing range from 4 candareens to 2 maces, and 5 candareens to 3 taels respectively, with a minimum scale of 2 li.

Figure 8 [Steelyard 2] It has one pivot, with a weighing range from 1 candareen to 2.2 maces, with a minimum scale of 1 candareen.

Later, even if the use of silver ingots declined and the traditional gold and silver shops and appraisal stores also bowed out, the hand steelyard, this Chinese ancient mechanical invention, was still used when the silver dollars were in wide circulation until the Republic of China period, which become a rare living fossil in the history of gold and silver monetary.

Figure 9 [Steelyard 3] It has two pivots, with a weighing range 1 mace to 1 tael and 2 maces to 9 taels respectively, with a minimum scale of 1 candareen.

Figure 10 [Steelyard 4] It has two pivots, with a weighing range from 1 mace to 1.5 taels, and from 1 tael to 2.3 taels respectively, with a minimum scale of 2 candareens.

Figure 11 [Steelyard 5] It has three pivots, with a weighing range from 1 candareen to 7.5 maces, 2 candareens to 3.5 taels, and 4 candareens to 11 taels, respectively, with a minimum scale of 1 candareen.

The way to identify the purity of gold and silver in the Tang and Song dynasties

As far as we know, the most detailed information on the analysis and identification of gold and silver purity is provided by The Identification of the Counterfeited Treasure (《寶貨辨偽》) from the end of the Southern Song dynasty. 2

In the section about gold, it writes "the purity of gold can be identified through the color presented by striking the gold on the touchstone, which method can examine the purity ranging from 5% to 100%." In addition, the technique of identifying whether or not low-purity gold or silver was used or encased was also known at that time from the hammer marks and the seams on the bottom of gold bars or goldware.

As for the silver, it writes "The back of a real silver ingot is flat as paper, the center is sunk, and the four corners are concave. The way to identify the purity of silver can only be understood but not expressed. If you can use it correctly, it will be exactly precise." "The silver content of jin qi hua yin [金漆花銀] silver ingot is 100%, nong diao hua yin [濃調花銀] 99.9%, cha hua yin [茶花銀] 99.8%, da hu hua yin [大胡花銀] 99.7%, bao hua yin [薄花銀] 99.6%, bao hua xi shen [薄花細滲] 99.5%, zhi hui hua yin [紙灰花銀] 99.4%, xi shen yin [細滲銀] 99.3%, lu shen yin [麄滲銀] 99.1%, duan shen yin [斷滲銀] 98.5%, and wu shen yin [無滲銀] 97.5%. As for silverware, jewelry, and bracelets, people like those in the popular style, so they are recast frequently, which makes the purity to be lower and lower. It is especially important to be careful when identifying the gold-plated silverware." What is noteworthy is that people in the Song dynasty could not only identify the purity from the appearance of silver ingots, but the subtle differences in features and color were also the basis for judging, with only 0.1% between the two purity grades. This kind of skill is amazing. Undoubtedly, this has laid an important foundation for the monetization of silver.

People learned a little about how to distinguish silver ingots gradually. Later, especially in the Ming and Qing dynasties, the money shops and the appraisal stores gathered the relevant know-how with great success, much of which was inherited from the experience in the Song dynasty.

Though the skill to identify the purity of silver was mature in the Song dynasty, the development of the gold and silver weighing technique was relatively slow, which might be the reason for the difficulty in the gold and silver monetization. This article will explore this issue that has not been noticed.

The invention and impact of steelyard in the Song dynasty

The wide use of the scale is attributed to the circulation of silver ingot, a currency valued by weight. The scale used in ancient China is an equal-arm balance (Figure 1). However, limited by manufacturing technology, the traditional scales cannot meet the two conditions required for weighing silver ingots. First, the weight unit of the scale must be small enough to weigh the mace and candareen to cope with various prices in transactions. Second, the size of the scale must be light enough to carry around.

|

Figure 1 Equal-arm scale used by the Qing dynasty government

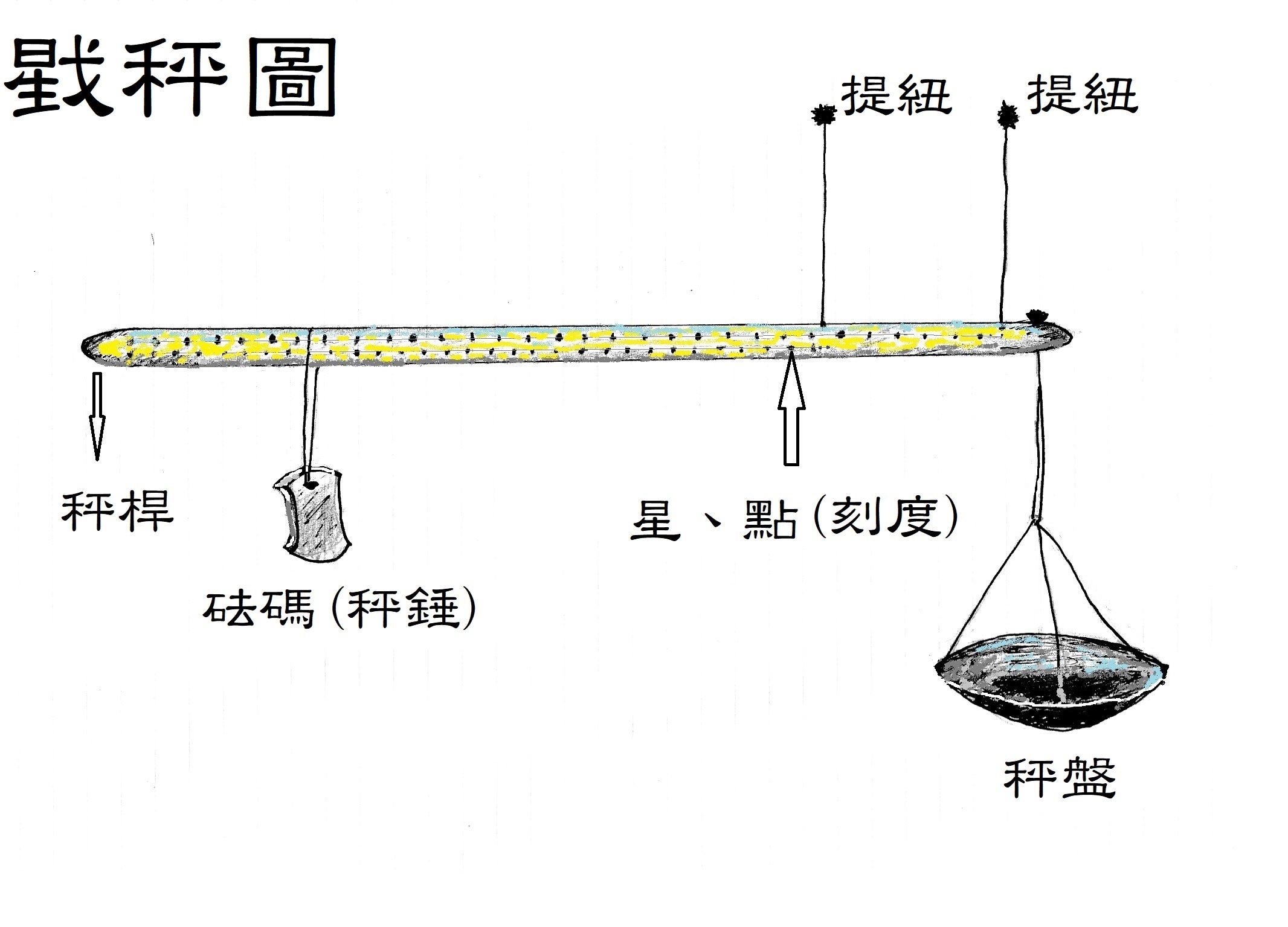

During the Jingde Emperor's reign of the Northern Song dynasty (1004-1008 A.D.), an elaborate and sufficiently accurate scale, a kind of steelyard called deng cheng [戥秤], was created (Figure 2). This new type of scale was invented by the court official Liu Chenggui (劉承珪)3. After years of development, gold and silver, but especially silver, came to be in general circulation in the Ming and Qing dynasties. The complete monetization of silver and gold is related to the maturity of the weighing technique which was developed on the basis of the steelyard from the Song dynasty.  |

Figure 2 Steelyard

Deng cheng is a non-equal-arm balance made according to the principle of leverage. It can weigh various items by moving the position of the weight, with very high accuracy. Such features make the scales light and compact. According to the records, Liu's steelyard has a some-40-cm balance beam weighing about one mace and a weight weighing six candareens. The beam has three pivots, with a weighing range respectively. The first pivot weighs from five candareens to 1.5 mace; the second from two candareens to one mace; and the third from one to five candareens. With continuous improvement, the smallest known steelyard4, which appeared around the end of the Ming and early Qing dynasties, has a balance bean of only 11 cm long. It can weigh as little as 1 candareen. It has two pivots to weigh one candareen to one mace and two candareens to 3.2 mace respectively. (See Figure 7, No.1 steelyard from the author's collection.)The steelyard was not commonly used in the Song and Yuan dynasties, so it was hard for gold and silver to circulate

However, because of the technical limitations of manufacturing, delicate steelyards for weighing micro-objects had been exclusive to the palace, while the early folk steelyard could only be used to weigh daily commodities, not suitable for precious gold and silver due to the large error margin and size. A Yuan-dynasty fresco featuring an officer weighing fish also reveals this situation (Figure 3). The Yuan was a dynasty that attached great importance to weights and measures, and the market was equipped with official scales to ensure fair trade; however, because of the immature weighing techniques, though the officer used an official steelyard, it was too big and inaccurate to weigh gold and silver but only used to measure the weight of daily objects.

|

Figure 3 A Yuan-dynasty fresco in Guangsheng Temple, Guangxi, featuring an officer weighing fish

Weight is another factor other than purity that determines the value of silver ingots. As for the silver ingots in circulation during the Song and Yuan dynasties, it is recorded that "currently, the big ingot is valued at 50 taels, the middle ingot 25 taels, and the small ingot half again".5 Due to undeveloped weighing techniques, 50 taels was used as the unit for a silver ingot at that time, with halving and then re-halving to be middle and small ingots as currency. However, the value of either one is quite high and not affordable for the general public. It is assumed that these ingots were mainly used in international and border trade and large commercial transactions because of the limited accuracy of scales and steelyards. |

Figure 4 British steelyard

At that time, there were few silver pieces weighing only one or two taels in circulation, which indicates that accurate steelyards for weighing gold and silver were still a precious resource, exclusive for the government and only a small number of people. During the Tang and Song dynasties, especially the Southern Song dynasty, society was flooded with large amounts of gold and silver for reasons such as mineral exploitation and overseas import, which made the road to monetization seemed to be open. However, as the Chinese expression says "the thunder was loud, while the rain was small". In other words, there was a lot of talk but little action and the monetization of gold and silver was still not realized in the end. This result is probably related to the fact that the small silver pieces could not be weighed, so transactions were hampered. In this way, private trading had to continue using cash coins and notes.Hand steelyards became a necessity in the Ming dynasty, which allows the silver to circulate in all walks of life

In the late Ming dynasty, silver was declared legal tender, and various silver ingots were circulated in all sectors of society. This result was made by the achievement of a variety of conditions. Among them, the birth of a kind of steelyard specifically for weighing gold, silver, medicine, and other precious items was crucial.

The steelyard for weighing gold and silver is compact, and the arms and weights can be stored in a small wooden box and carried around, which is the reason why it is called a hand steelyard which means it is portable. (Figure 5)

|

Figure 5 Various hand steelyards from the Ming dynasty onwards

Soon after, the hand steelyard became a handful of necessities, thus solving the long-existing problem that silver could not be weighed. As you could value silver pieces regardless of size by weighing them at any time and any place, the hand steelyard was quite popular. It was easier than ever to trade in silver, which transformation allowed silver to pass unhindered through both the public and private economies, fully performing its monetary function.

In the late Ming dynasty, local silver ingots sprang up all over the country. These small silver ingots of various shapes and sizes are mostly less than 10 taels or even 1 tael, and a large number of silver pieces at the weight of less than one mace were circulating on the market6. The hand steelyards were designed in response to the silver in actual circulation at the time. There were all kinds of hand steelyards that could weigh items lighter than 10 taels, and even mace and candareens (figure 6).7 Some of these steelyards are illustrated below. ((figure 7-11)

|

Figure 6 Silver pieces which could be weighed by hand steelyards in the Ming and Qing dynasties

The hand steelyard did not fade out of the market with the silver ingots but continued to be used for weighing silver dollars

In addition to silver ingots, silver dollars flowed into China starting from the late Ming dynasty and became very popular in the Qing dynasty. Later, the Chinese silver dollars were also put into circulation. Although the weight of these vintage coins was consistent when they were minted, their weight was always reduced due to the prevalence of filing and chopping on silver coins. Therefore, the value of the circulating coins must be decided after weighing.8 Thus, hand steelyards were not only used for weighing silver but later had more applications in the process and transactions of silver dollars.

Although both silver dollars and small silver pieces can be weighted with the same hand steelyards, exclusive designs for silver dollars can still be found on some hand steelyards. The Steelyard 5 shown in Figure 11 is an example. This hand steelyard presumed to date from the late Qing dynasty was made by Anlan Money Shop in Guangzhou. At that time, Guangzhou mainly used silver dollars, while silver ingots were rarely used, so the design of hand steelyards took into account the weighing target of silver dollars as the priority rather than the silver ingots. For this reason, the smallest weight scale among the three pivots of the hand steelyard, with an upper limit of 7.5 mace, can be said to be designed specifically for silver coins. One silver dollar weighs about 7.2 mace, so the pivot can be used as long as it is a silver dollar or a factional silver coin, without the trouble of changing the pivots in the process of weighing (Figure 12). As for the other pivots, the upper limit of the weight range is 3.6 taels and 11 taels respectively, which is about the weight of 5 and 15 silver dollars respectively. In addition, at the end of the Qing dynasty, Guangdong still minted local square trough sycees, with a unit weight of about 10 taels,9 which could also be weighed by this kind of hand steelyard.

|

|

Later, even if the use of silver ingots declined and the traditional gold and silver shops and appraisal stores also bowed out, the hand steelyard, this Chinese ancient mechanical invention, was still used when the silver dollars were in wide circulation until the Republic of China period, which become a rare living fossil in the history of gold and silver monetary.

|

|

|

|

Figure 12 Steelyard 5 has a pivot designed for weighing silver dollars

Note:

1 (Japan) Kato Shigeru, A Study of Gold and Silver in the Tang and Song Dynasties.

2 The Complete Collection of Essential Things for the Home, Volume 5, late Southern Song dynasty.

3 Qiu Guangming, The History of Ancient Chinese Metrology, Anhui Science and Technology Press, 2/1/2012.

4 Shi Youyong, Linxia, Steelyard Collector Ma Qingping, China Social Science Network, 2/25/2015.

5 Hu Sansheng, Identifying Errors in Annotations.

6 Stephen Tai, A Study on Square Trough Sycee: To Explore the History of Silver Ingots.

7 From time to time, examples of weighing silver pieces can be found in Ming and Qing dynasty novels. The case is the 51st chapter of the Dream Of Red Mansions (《紅樓夢》). It writes, "Sheyue then took a piece of silver, lifted the steelyard and asked Baoyu: 'Is this one tael?'" The eighth chapter of The Scholars (《儒林外史》)writes, "Mr. Qu said: 'It is the sound of the weighing with steelyard, the sound of the abacus, and the sound of the clapper.'" Another example is Three Heroes and Five Gallants (《三俠五義》). Its fifth chapter writes, "Mr. Bao turned around and asked Bao Xing to get the steelyard. Bao Xing answered, and hastened to get a steelyard. It indeed weighed one tael and eight mace."

8 Stephen Tai, Organized Chaos - The Model of Chopmark on Foreign Coins, Journal of East Asian Numismatics, Issue 28.

9 Stephen Tai, A Study on Square Trough Sycee: To Explore the History of Silver Ingots.

Note:

1 (Japan) Kato Shigeru, A Study of Gold and Silver in the Tang and Song Dynasties.

2 The Complete Collection of Essential Things for the Home, Volume 5, late Southern Song dynasty.

3 Qiu Guangming, The History of Ancient Chinese Metrology, Anhui Science and Technology Press, 2/1/2012.

4 Shi Youyong, Linxia, Steelyard Collector Ma Qingping, China Social Science Network, 2/25/2015.

5 Hu Sansheng, Identifying Errors in Annotations.

6 Stephen Tai, A Study on Square Trough Sycee: To Explore the History of Silver Ingots.

7 From time to time, examples of weighing silver pieces can be found in Ming and Qing dynasty novels. The case is the 51st chapter of the Dream Of Red Mansions (《紅樓夢》). It writes, "Sheyue then took a piece of silver, lifted the steelyard and asked Baoyu: 'Is this one tael?'" The eighth chapter of The Scholars (《儒林外史》)writes, "Mr. Qu said: 'It is the sound of the weighing with steelyard, the sound of the abacus, and the sound of the clapper.'" Another example is Three Heroes and Five Gallants (《三俠五義》). Its fifth chapter writes, "Mr. Bao turned around and asked Bao Xing to get the steelyard. Bao Xing answered, and hastened to get a steelyard. It indeed weighed one tael and eight mace."

8 Stephen Tai, Organized Chaos - The Model of Chopmark on Foreign Coins, Journal of East Asian Numismatics, Issue 28.

9 Stephen Tai, A Study on Square Trough Sycee: To Explore the History of Silver Ingots.