The source of the problem

The Kashgar Guangxu silver coin, which had been minted since A.H. 1309, has been highly valued by collectors of Sinkiang coins for its long minting period and many varieties. Different varieties minted in different Muslim years have become a focus for many collectors. I have been collecting Sinkiang coins for many years, and I am very interested in the undated Guangxu three-mace silver coin. I dreamed of seeing one, but I have had no such luck.

This variety first appeared in the Record of Xinjiang (新疆圖志) by Wang Shunan (王樹楠). It says, "In the eighteenth year of Guangxu's reign (A.H. 1309), Kashgar Intendant Li

Zongbin (李宗賓) ordered alternate county magistrate Luo Zhengxiang (羅正湘) to undertake a trial minting of Guangxu silver coins. Initially, the coins had three different denominations, namely, three mace, two mace, and one mace. In A.H. 1310, five-mace coins were also struck." By comparing the coins in kind, no undated Guangxu five-mace silver coin has been found. It is known that one-mace, two-mace, and three-mace undated varieties were indeed minted in A.H. 1309 by Luo under the order of Li.

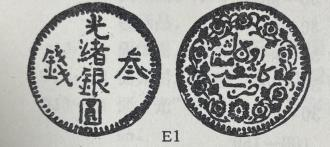

In the process of collecting, it is not difficult to find undated Guangxu two-mace and one-mace coins. However, I have only seen a not-so-clear rubbing of an undated three-mace coin in the Illustrated Catalogue of Sinkiang Gold and Silver Coins many years ago (Fig. 1). I visited many senior collectors, trying to find an undated three-mace coin. They all say, "I have collected coins for many years, but I have only heard about the undated three-mace coin, but I have never seen one." As a coin with a clear official record, it has had an extremely rare exposure over the centuries, and its mysterious aura has drawn me to find the truth.

To find the answer

Based on my experience of collecting Sinkiang coins, I do not think that the coin in the rubbing is the undated Guangxu three-mace coin minted in A.H. 1309. The reasons are as follows.

1. Through my observation, the Chinese characters on the obverse in Figure 1 are very similar to those on the obverse of the A.H. 1311 Guangxu three-mace silver coin. There are only two differences on the reverse as shown in the red circle in Fig. 2. It is not logical for the A.H. 1309 undated three-mace coin to use the same obverse die as the A.H. 1311 one minted two years later.

2. Because it was common for the Sinkiang coins to be struck with mixed dies, it is possible that the undated three-mace coin shares the same obverse die with the A.H. 1311 Guangxu three-mace coin. Yet, this speculation can be easily disproved by comparing the obverse of the A.H. 1310 three-mace coin (Fig. 3).

The obverse of the A.H. 1310 three-mace coin is characterized by smaller characters and the "厶" of the character "叁" is in the center, which is distinctly different from the larger character of the A.H. 1311 one with the "厶" to the right (Fig. 4). The Kashgar Mint designed the coin dies with traceable changes from year to year, so it is impossible for an A.H. 1311 three-mace coin to have been minted with the obverse die of the A.H. 1309 undated three-mace coin. Therefore, the rubbing is questionable.

Fig. 1 Rubbing of undated Guangxu three-mace silver coin

Fig. 2 A.H. 1311 Guangxu three-mace silver coin

3. The reverse of Figure 1 shows that although the coin does not have the Muslim date, there is an empty space where the year should have been inscribed, which is not in line with the compact design style of the Kashgar coins. Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 are pictures of undated two-mace and one-mace coins in my collection. The leaves and Uyghurche characters are tight on the reverse, with no space for the Muslim date when the dies were made. Thus, it is unreasonable for the designer to leave space for the year on the die of the undated three-mace coin.

4. The evidence begins to point to the fact that the rubbing of the undated three-mace coin is most likely an altered coin made by scratching off the year on the reverse of the A.H. 1311 three-mace coin. Due to the inconvenient communication of information decades ago, collectors in Sinkiang have embraced the coin as authentic, and its rubbing has been passed down to this day.

Fig. 3 A.H. 1310 three-mace coin

Fig. 4 A.H. 1311 three-mace coin

Conclusion

Over the past hundred years, information on the minting of Sinkiang coins has been either lost or is incomplete, making it difficult for the coin catalogs published in earlier years to fully show the true history. It is also a great pleasure for collectors to question authoritative catalogs based on existing coins.

As the research in this paper is very elementary, it can only be speculated that the coin of the rubbing of the undated three-mace coin that has been circulating for many years is suspicious of being a forgery or altered coin. We cannot directly deny the existence of an undated three-mace coin, therefore, this paper has been written to draw readers' interest to the study of Sinkiang coins and to make a modest contribution to the resolution of this historical mystery. Perhaps a real undated Guangxu three-mace silver coin is just lying quietly in a corner of boundless Western China, waiting to be discovered.

I would like to express my gratitude to Mr. Chen Li of Chengdu and Mr. Gan Yong of Nanjing for their help in writing this paper.

|

|

|

Fig. 5 Reverse of the undated

two-mace coin |

Fig. 6 Reverse of the undated ne-mace coin |